Last updated June 6, 2023.

Table of Contents

Digital Minds and Artificial Sentience Wild Animals and Invertebrates Our Approach and Theory of Change |

Moral Circle Expansion

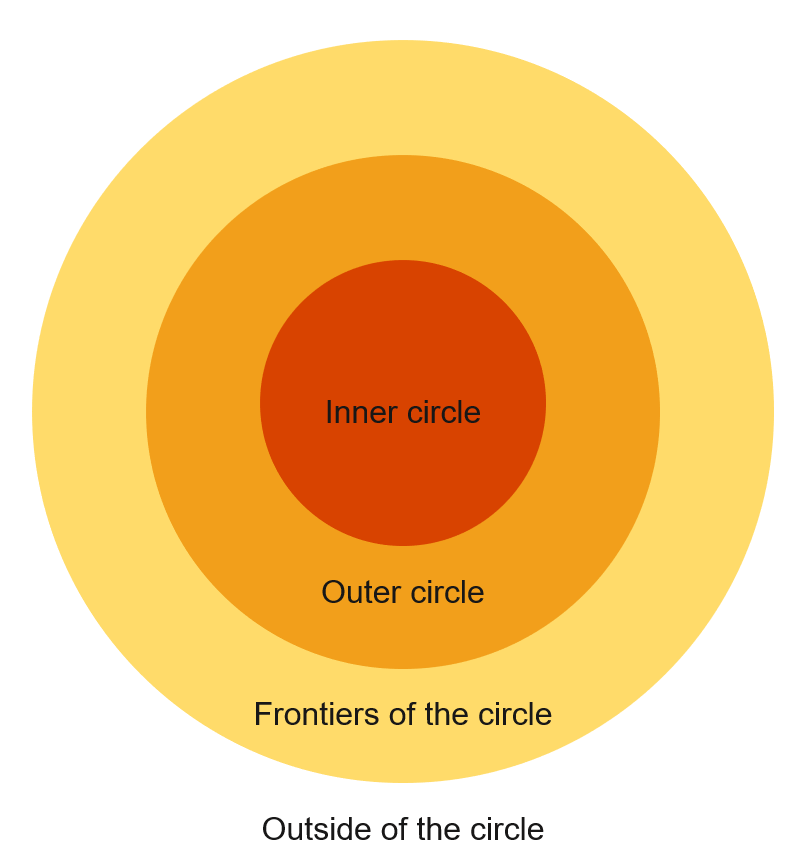

The main focus of our research at Sentience Institute is the moral circle, a concept introduced by Lecky (1869) and popularized by Singer (1981) that refers to the boundary around entities that are granted moral consideration. At the most basic level, we conceptualize it as a series of concentric circles, as shown in Figure 1. Entities in the inner circle are granted full moral consideration: their interests are fully taken into account in moral decision-making. Entities in the outer circle are granted a moderate level of moral consideration, but their interests are devalued relative to those in the inner circle. At the frontiers of the circle, entities are granted minimal moral consideration, and those outside of the circle are granted no moral consideration at all. Any entities can be included in this model, such as humans, animals, robots, and ecosystems.

Figure 1: The Moral Circle. This conceptualization draws on Crimston et al. (2018).

We can distinguish between several conceptions of the moral circle. We can consider a person’s attitudinal, or self-reported, moral circle — what they think their moral circle should look like, and their behavioral, or choice-based, moral circle — how they treat other entities. We can also distinguish between an individual’s personal moral circle — how they personally act (or think they should act) towards different entities, and the societal moral circle — how society as a whole treats different entities, or how people think society should treat different entities. Moreover, in most conceptions, it is not a circle per se. It spans across many dimensions and has holes and protrusions, such as apparently distant groups that are given uniquely high moral concern, and gradients rather than distinct categories of concern. Consider, for example, the treatment of bald eagles in the U.S., where they are a national bird and symbol, despite birds generally being on the frontiers or outside of the moral circle.

At Sentience Institute, we are mainly interested in the societal moral circle. This captures the laws, policies, and norms that are intended to protect the interests of different entities. We envision a society where all sentient beings, that is, beings with the capacity for positive and negative experiences, are included in the inner moral circle. Note that this does not mean we think all sentient entities should be treated in exactly the same way. Different entities have different interests. Being in the inner circle means an entity’s specific set of interests are given full moral consideration, not that they are treated in exactly the same way as others in the circle.

Currently, society’s moral circle looks quite different from our vision of all sentient beings in the inner circle. The actual moral circle spans across many dimensions other than sentience. For example, society grants moral consideration based on factors such as an entity’s location in space, their location in time, their species, their substrate, whether their experience is the result of an act or an omission, the cause of the entity’s experience, and what an entity is believed to deserve.[1] Intrinsically, Sentience Institute considers all of these factors to be irrelevant, though there may be instrumental reasons to care about some of them if doing so would benefit sentient beings. Finally, while we envision a society in which the moral circle includes all sentient beings, it is important to note that this does always mean working directly toward moral circle expansion because it could be in some cases that doing so would not maximize positive impact — see the following sections for more detail.

We describe the moral circle and its prioritization in more detail in our 2021 paper in the journal Futures, “Moral Circle Expansion: A Promising Strategy to Impact the Far Future.”

Effective Altruism

How should we approach the task of expanding society’s moral circle to include all sentient beings? At Sentience Institute, we apply the principles of effective altruism to help us answer this question. Effective altruism aims to generate the most positive impact with the available resources. Ideally, we would help all sentient beings that need it right away, but in reality, resources are scarce and we must make decisions about how to allocate them.

Having the largest impact with our resources requires us to define what we mean by “impact.” Sentience Institute is focused on the wellbeing of sentient entities. We take a broadly utilitarian approach. Still, we think that an important way of respecting the interests of sentient beings is by recognizing them as legal persons, such as the endowment of legal rights and standing. This has been one of the main methods of moral circle expansion for humans; we’ve seen this with the abolition of slavery, the passage of child labor laws, the franchisement of women, and many more important social movements. In each of these cases, the granting of legal rights greatly increased wellbeing, and it would likely do so for nonhuman sentient beings as well.

An important view associated with effective altruism is longtermism, that vast amounts of moral value exists in the long run, so we ought to take steps to ensure that it goes as well as possible. In practice, this often involves working to reduce existential risk — x-risks. Given the size of the long-term future, and the potential for humanity’s expansion beyond earth, a particularly important consideration is s-risks — risks of astronomical suffering, on a scale far exceeding anything that currently exists on earth today. Preventing s-risks is an important priority from the perspective of suffering-focused ethics. At Sentience Institute, we take a longtermist perspective on moral circle expansion, prioritizing the wellbeing of sentient entities in the long run rather than the next few months or years, with a particular focus on avoiding extremely negative outcomes.

Finally, we are concerned with our expected impact. Since the benefits we hope to create lie in the future, which is necessarily uncertain, we consider the right actions to be the ones that are most likely to bring about those benefits. In practice, calculating how to have the largest expected impact over the long run is largely infeasible. Rather than carrying out such calculations explicitly, we tend to rely on heuristics, such as the scale, neglectedness, and tractability of a problem, which is common in effective altruism.

Promising Cause Areas

Within the general project of moral circle expansion, the following frontiers of the moral circle seem particularly important as cause areas.

Digital Minds and Artificial Sentience

Most of our current work focuses on digital minds with mental capacities such as emotion, autonomy, socialization, meaning, language, and self-awareness, related to what Holden Karnofsky calls “digital people.” Of particular interest is artificial sentience — that is, sentient beings whose minds are instantiated in artificial or digital substrates. While this may seem like a farfetched concern, particularly given the scale and intensity of suffering that exists on the planet today, there are several reasons to take the possibility seriously. Taking a longtermist perspective requires asking what sentience will look like in the very long run.

First, there is a trend towards increasingly advanced artificial intelligence. This is due in part to increasing computer power and data availability, which means that increasingly complex learning algorithms are being developed and used to solve a growing range of social problems, and due to groups such as OpenAI and DeepMind trying to create of artificial general intelligence. Future artificial entities may have features that we typically associate with sentience, and in some cases, this is an explicit goal.

The nature of digital minds — the ease with which they can be created and copied, for instance — makes it possible that they will be created in extremely large numbers. There is also reason to think these entities may not be fully included in humanity’s moral circle, particularly because while some artificial entities may have humanlike features, others are likely to be quite different to humans and thus prone to exclusion as many nonhuman animals are today. This could lead to their mistreatment, either incidentally, because their interests are not given sufficient attention, or deliberately, as a result of the actions of malevolent agents. It may be very difficult to align AI systems with human interests if AIs are not included in humanity's moral circle or, worse, if there is active conflict or animosity between humans and AIs.

For more information on digital minds, see our blog post, “Key Questions for Digital Minds.” For more specifically on the case for working on artificial sentience issues, see our blog post, “The Importance of Artificial Sentience.” For more information on the current scholarly work on moral consideration, see our 2021 Science and Engineering Ethics paper, “The Moral Consideration of Artificial Entities: A Literature Review.”

Farmed Animals

There are over 100 billion land animals on farms right now, and the overwhelming majority — 99% in the US and over 90% globally — are crowded in inhumane facilities known as “factory farms.” The intensive confinement of animals on these farms leads to a range of psychological and physical health problems, and many of these animals endure painful deaths on account of health complications caused by their breeding or environment. Some animals are debeaked, castrated, or mutilated in other ways without anesthesia. The stunning methods used to knock some animals unconscious before slaughter fail regularly, and errors on industrial slaughter lines result in atrocities such as nearly one million birds being boiled alive every year. Nearly all fish die by being painfully suffocated and crushed by other fish in nets that pull them out of the water.

These are just some examples of the suffering farmed animals experience. While there are some laws in place to protect their interests, society has a long way to go before farmed animals are granted full moral circle inclusion. Moreover, attention to farmed animal welfare is highly neglected — even when we only consider the limited resources that society directs to nonhuman animal issues, a small proportion goes towards farmed animals. Practically, addressing this issue is relatively tractable — we can pass laws and policies, influence social norms to reduce meat consumption, and create animal-free food products, all of which tend to reduce the suffering of farmed animals.

While we are most concerned about the scale and intensity of suffering involved on factory farms, we favor the full transition away from animal farming to a completely animal-free food system. This is for several reasons, including the fact that so-called “humane” farms often still cause significant harm to nonhuman animals. Further discussion on the case against “humane” farming can be found in a book excerpt in The Guardian, and a more general discussion of the problems of and solutions to animal farming can be found in our book, The End of Animal Farming.

Wild Animals and Invertebrates

While the number of farmed animals in existence is in the hundreds of billions — an incomprehensibly large number to intuitively grasp — the number of wild animals in existence is orders of magnitude larger with wild birds and mammals in the trillions and insects potentially in the quintillions. Humans tend to grant consideration to only highly charismatic animals in the wild, such as pandas, elephants, and blue whales, or show concern only through more abstract categories such as species, ecosystems, and habitats. Concern for the wellbeing of less charismatic wild animals as individuals with their own set of interests, however, is highly limited. This may be due to the sheer number of wild animals in existence, as well as an idealized vision of life in the wild that does not take into account the widespread existence of illness, hunger, predation, and other natural causes of suffering. Since we at Sentience Institute care about the wellbeing of sentient beings, the widespread existence of suffering in the nature raises the question of what can be done about it.

This topic has been receiving greater attention in academia and from nonprofit organizations in recent years, and a healthy discourse has emerged. Given the complexity and interconnected nature of ecosystems, any attempt to intervene with the goal of benefiting wild animals can easily lead to unintended consequences. Much of the current work, therefore, is focused on gaining a better understanding of the issues at stake, and in some cases carrying out small scale interventions, such as administering contraceptives to manage resource availability, to understand the effects on wild animals’ lives.

Sentience Institute does not currently have specific research projects on wild animal suffering, though we may in the future. For further information on this topic, we recommend the work of Animal Ethics, Rethink Priorities, and Wild Animal Initiative.

Future Beings and Longtermism

The farmed animals, wild animals, and artificial entities who can be helped are mostly those who exist in the future, arguably in the long-term future, but it is worth briefly considering “future beings” as a category in itself. While we consider artificial sentience to be a key risk from a longtermist perspective, we also think it is important to consider future generations of beings more generally, such as humans and non-human animals, given that they are also largely excluded from humanity’s current moral circle. From a longtermist perspective, we should not only take into account the wellbeing of the next few generations of beings, but of all future generations.

There are a range of risks that may affect the wellbeing of all sorts of future beings, such as climate change, nuclear war, and pandemics. Again, artificial intelligence has the potential to radically transform society over the next few decades or centuries. The specifics of such a transformation are uncertain, but society’s future institutions, including those affecting its moral circle, could be determined by the goals and values that are specified, either correctly or incorrectly, in very powerful AI.

For a discussion of different strategies to affect the long-term future, see our 2018 post, "Why I Prioritize Moral Circle Expansion over Artificial Intelligence Alignment." For a discussion or the expected value of the long-term future, see our 2023 post, “The Future Might Not Be So Great.”

Our Approach and Theory of Change

At Sentience Institute, we approach issues of digital minds and moral circle expansion through research. The research we conduct is interdisciplinary, particularly across economics, history, philosophy, psychology, and sociology. We focus on empirical questions, such as how the moral circle has expanded historically, what people’s moral circles look like today, and the factors that influence people’s moral circles, but also work on some conceptual questions to clarify concepts such as sentience and moral circle expansion. Historically, we have focused on farmed animals; we now allocate a substantial proportion of our resources to address questions related to artificial sentience.

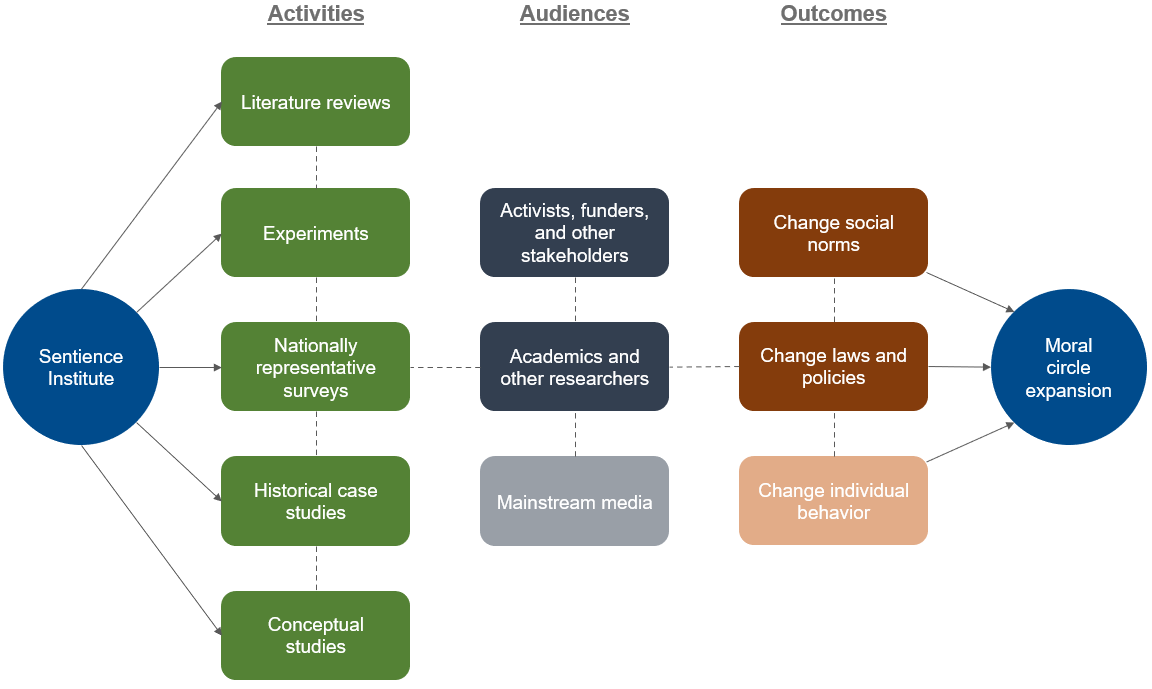

Our research has many different routes to impact, often referred to as the “Theory of Change.” Most directly, we aim to discover the factors (e.g., activism and business strategies) that most lead to positive impact, but we also aim to understand the nature of moral progress (e.g., How do more people become longtermist?) and evaluate the extent to which certain moral and social outcomes should be prioritized by those trying to do the most good (i.e., “global priorities research”). This helps activists, donors, investors, governments, firms, and other stakeholders working on these issues gain the knowledge required to implement strategies that will change social norms and implement more morally inclusive laws and policies. While we mainly focus on institutional change, we expect our research will also help organizations working on changing individual behavior. Because of our longtermist perspective, we are interested in helping develop social movements and organizations that can take action many years from now.

Where appropriate, we publish our research in academic journals, which helps communicate our findings to academics and encourages other researchers to carry out similar research. Our research sometimes attracts media attention, which we expect also has positive effects by informing public opinion and promoting more morally inclusive social norms. Usually, stakeholders see our research via email or directly on our website.

Figure 2 summarizes this Theory of Change, how we expect our research to lead to a better future for all sentient beings.

Figure 2: Sentience Institute’s Theory of Change. Higher opacity indicates higher priorities. This figure is partly inspired by Faunalytics.

[1] For example, the existence of global extreme poverty, climate change, and factory farming imply that society grants moral consideration based on entities’ physical location, their temporal location, and their species, and notions such as moral desert are built into many legal systems.