Edited by Kelly McNamara. Many thanks to the researchers who provided feedback or checked the citations of their work: Matthew Anderson, William Low, Sushil Mohan, Margaret Levi, Mark Hudson, and Geoff Moore.

Abstract

This report aims to assess (1) the extent to which the international Fair Trade movement, especially from 1964 to the present, can be said to have successfully achieved its goals, (2) what factors caused the various successes and failures of this movement, and (3) what these findings suggest about how modern social movements should strategize. The analysis highlights strategic implications for a variety of movements, especially those focused on moral circle expansion. Key findings of this report include that engaging directly with mainstream market institutions and dynamics can enable a social movement to influence consumer behavior much more rapidly than efforts to build “alternative” supply chains, though such mainstream engagement may also lead to co-option and a lowering of standards; and social movements may need to prioritize strategies to resist pressure from private sector businesses to weaken the standards of certified products.

Table of Contents

Introduction

One definition of Fair Trade, jointly agreed by several international Fair Trade organizations, is:

[A] trading partnership, based on dialogue, transparency and respect, that seeks greater equity in international trade. It contributes to sustainable development by offering better trading conditions to, and securing the rights of, marginalized producers and workers—especially in the South. Fair trade organisations (backed by consumers) are engaged actively in supporting producers, awareness raising and in campaigning for changes in the rules and practice of conventional international trade.[1]

The nonprofits, activists, and mission-driven businesses promoting this kind of trading partnership comprise the “Fair Trade movement.”[2]

The Fair Trade movement’s intended beneficiaries are “disadvantaged producers” in the Global South.[3] Fairtrade International (also known as Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International or FLO), summarizes that, for participating producers, Fair Trade means:

- “Prices that aim to cover the average costs of producing their crop sustainably – a vital safety net when market prices drop

- The Fairtrade Premium – an extra sum of money paid on top of the selling price to invest in business or community projects of their choice

- Decent working conditions and a ban on discrimination, forced labour and child labour

- Access to advance credit ahead of harvest time

- Being able to plan more for the future with more security and stronger relationships with buyers.”[4]

Consumers and institutions in the Global North are the key audience of the Fair Trade movement. For example, 97% of the Fair Trade retail sales value in 2017 reported by FLO came from countries in North America, Europe, and Oceania.[5] Hence, this movement supports, at least in part, an expansion of the moral circle of people in the Global North to encompass geographically distant human beings. Although there are differences between the Fair Trade movement and other social movements focused on moral circle expansion, such as the farmed animal movement, these other movements can glean some strategic insight about which strategies are most effective from the history of Fair Trade.[6]

This case study has a broader geographic focus than Sentience Institute’s previous four social movement case studies,[7] primarily because there is often limited evidence or information about Fair Trade in individual countries. Otherwise, this report uses similar methodology and framing to SI’s previous case studies.[8]

This report uses the term “co-option” to refer to the idea of stakeholders replicating some aspects of Fair Trade without fully adopting its ideals. This is similar to the usage by sociologist William Gamson, who defined success for social movement organizations in terms of either “acceptance” by their antagonists or “new advantages” accrued for their intended beneficiaries; “co-optation” (co-option) is where an organization or movement achieves “acceptance” but not “new advantages.”[9] The terms “Global North” and “Global South” are used, following recent scholarly usage.[10] The meaning is similar to the terms “developed” and “developing”; the former category contains North America, Europe, Australia, and a handful of other countries (such as Japan, South Korea, and Israel), while the latter term includes most of Asia, Central America, South America, and Africa. “Northern” and “Southern” are used as the adjectives for these terms.

From the 1990s, coffee became an important part of the Fair Trade movement’s product mix.[11] Many scholars focus primarily on coffee when evaluating the Fair Trade movement.[12] Given the greater availability of evidence and analysis for this product type, sometimes this report discusses Fair Trade coffee assuming that it is fairly representative of Fair Trade foodstuffs more widely. Note, however, that there may be differences from product to product, and the movement sells a larger volume of Fair Trade bananas than coffee.[13] Many scholars also focus primarily on the movement in the UK,[14] though this seems more clearly justified, given that the UK sells the most Fair Trade products.[15]

Summary of Key Implications

A single historical case study does not provide strong evidence for any general claim on social change strategy; the value of these case studies comes from providing insight into a large number of important questions.[16] This section lists a number of strategic claims supported by the evidence in this report:

- Engaging directly with mainstream market institutions and dynamics will enable a social movement to influence consumer behavior much more rapidly than efforts to build “alternative” supply chains.

- Engaging directly with mainstream market institutions and dynamics may lead to co-option and a lowering of standards.

- Social movements should implement strategies to resist pressure from private sector businesses to weaken the standards of certified products.

- Social movements should seek to minimize the number of competing certification schemes.

- Certification schemes may be ineffective or counterproductive in high-priority countries.

- Marketing efforts likely increase awareness and purchases of certified products, but high awareness and support do not necessarily lead to widespread changes in consumer behavior.

- Individuals who participate in consumer action are more likely to participate in other forms of activism.

- Social movements engaging with market mechanisms may be able to draw substantial funding from for-profit organizations.

A Condensed Chronological History of the Fair Trade Movement

Early history of Fair Trade

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, there were likely several examples of companies that implemented policies resembling those of the more recent Fair Trade movement, such as The Hamodava Tea Company, set up in 1899 by the Salvation Army, which sought to pay farmers fair prices and enable them to buy the land that they worked on.[17]

There have been previous examples of ethically motivated “buycotts,” which urge consumers to purchase ethically preferable goods. These include the US “white label” campaigns in the late 19th and early 20th centuries which encouraged the purchase of goods certified by Consumers’ Leagues rather than goods produced by workers in poor conditions.[18] There have also been efforts to alter the norms of exchange more broadly, such as the Co-operative movement of the 19th century onwards[19] and various efforts in the Global South to support producers and create alternatives to international trade.[20]

In the 1940s and 1950s, Christian groups began selling craft goods to support marginalized peoples and refugees:

- The Mennonite Central Committee started Self Help Crafts (later called Ten Thousand Villages) in 1946 to support Palestinian refugees and people from Puerto Rico and Haiti; initially Puerto Rican needlework was bought and sold onwards in the US.[21]

- In 1949, Sales Exchange for Refugee Rehabilitation and Vocation (SERRV) began selling handicrafts from displaced European refugees[22] to US members of the Church of the Brethren.[23] The organization also traded with poor communities in the Global South.[24]

- In the 1950s, Oxfam sold handicrafts made by Chinese refugees alongside secondhand goods; Oxfam had been started in 1942 by Quakers and other religious groups to feed the hungry in Greece.[25]

- In the Netherlands, Catholic group Fair Trade Organisatie (originally known as S.O.S. Wereldhandel) began selling handicrafts produced by Southern artisans.[26]

- In the late 1950s, Dutch Catholic activists started selling cane sugar, saying that this would “give people in poor countries a place in the sun of prosperity.”[27]

1964-88: Alternative trade

Over the course of the second half of the 20th century, global levels of trade and inequality both increased substantially.[28] In 1964, the dissatisfaction of governments in the Global South with existing international trade institutions led to the creation of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).[29] At the UNCTAD Conference in 1968, in Delhi, developing countries called for “Trade not Aid” to address their problems.[30] Their demands were rejected,[31] but the calls for fairer international trading may have influenced the nascent Fair Trade movement.[32]

In 1964, Oxfam created Oxfam Trading, the first Alternative Trading Organization (ATO).[33] ATOs have been defined as “nonprofit businesses that market crafts, gifts, and food from developing countries… Combining functions of exporters and retailers, ATOs work directly with producer groups on product design, quality control, management, and shipping.”[34] Dutch groups sold handicrafts from the Global South and opened the first “world shop” in 1969.[35] The world shop model — selling artisanal and Fair Trade products from the Global South — seems to have spread fairly rapidly in Europe.[36] These world shops seem to have been intended at least partly to raise awareness of development issues and the ideals of the Fair Trade movement.[37] By 2005, there were over 2,800 world shops in Western Europe.[38] However, business scholar Matthew Anderson notes that, in the 1960s and early 1970s, Oxfam Trading and other ATOs “were not offering wages any better than the market rate, they did not make advance payments and did not give producers any commitment to long-term development.”[39] Initially, the only evidence of the “fairness” of alternative trade that was readily available to consumers came from the claims and assurances made by the importers and retailers themselves.[40]

During the 1960s and 1970s, NGOs and socially motivated individuals in Asia, Africa and Latin America established Fair Trade organizations and made connections with the new organizations in the Global North, seeking greater equity in international trade.[41] During the 1970s, earnings from exports of raw materials stagnated, and the influence of multinational corporations in international trade expanded, perhaps increasing the apparent need for fairer trading systems.[42]

In 1973, the Dutch organization Fair Trade Organisatie imported the first Fair Trade coffee from cooperatives of small farmers in Guatemala.[43] Over the next decade or so, other Fair Trade food products began to be sold, such as “Campaign” coffee in the UK.[44] Alongside this development, alternative trade in handicrafts continued to grow.[45] The first European World Shops conference occurred in 1984.[46]

Equal Exchange, the US’ first Fair Trade company, was founded in 1986.[47] Equal Exchange was (and still is) a cooperative, focusing first on exploiting a loophole in the Reagan administration’s ban on imports from Nicaragua in order to support Nicaraguan farmers; the founders used lawyers and a political campaign to resist restrictions.[48] In 1987, the European Fair Trade Association (EFTA) was created, comprising the 11 largest importing Fair Trade organizations in Europe.[49] Subsequently, numerous regional networks of Fair Trade organizations have been established.[50]

1988-97: Product certification and the switch from handicrafts to foodstuffs

Business scholars William Low and Eileen Davenport cite claims from the International Federation of Alternative Trade that, by the late 1980s, growth in the number of new Fair Trade organizations and in sales volumes had slowed significantly.[51] Additionally, in the 1990s, some Alternative Trading Organizations began to lose money.[52] The following factors contributed to these developments:

- A reduction in tariff barriers which enabled competitors to sell lower-cost clothing and other goods that used materials and styles from the Global South.[53]

- A global recession in the mid to late 1980s which reduced Northern consumers’ willingness to pay for Fair Trade items.[54]

- The increasing demands of consumers and health and safety regulators in the Global North, which increased costs.[55]

- The inefficient operating models of many ATOs.[56] This probably meant that the handicrafts they sold were expensive and appealed mostly to a niche group of privileged consumers.[57]

Fair Trade products continued to be sold mainly in niche “Fair Trade Shops” in the US and Europe,[58] though in the years to come, the movement shifted away from handicrafts towards a focus on foodstuffs. At a similar time, there was a shift in discourse in the movement from “alternative trade,” an idea associated with non-mainstream distribution channels such as world shops and with broader social justice campaigns, to “fair trade,” an idea focused on mainstream consumerism and fair prices for producers.[59]

In addition to the decline in handicraft sales, a number of other factors outside the direct control of the Fair Trade movement may have encouraged these two shifts:

- The failure of international institutions’ efforts to create a fairer trading system and a rise in neoliberal, free trade policies.[60]

- The rhetoric of neoliberal politicians, which emphasized the power of consumer action.[61]

- The broader rise in ethical consumerism evidenced by various consumer surveys and purchasing data.[62]

- The increased media attention and public awareness of other issues of corporate social responsibility in the 1990s, such as the use of sweatshops.[63]

- A fall in the price of green coffee beans from around $1.30 per pound to below $0.60 while the cost of production remained around $1.10, which created financial difficulties for coffee producers. The decrease was encouraged by a deadlock within the International Coffee Organization and failure to negotiate a new International Coffee Agreement between 1989 and 1994, by which point it commanded lower international influence.[64]

In 1988, Dutch activists and Mexican smallholders who grew coffee created the first Fair Trade guarantee label, Max Havelaar, to certify products that met their standards and facilitate Fair Trade products’ introduction into mainstream retailers.[65] Within a few years, Max Havelaar-certified coffee seems to have represented around 2% of the Dutch coffee market.[66] Activists pressured supermarkets to introduce Max Havelaar coffee,[67] and by 1990, 89% of Dutch supermarkets had done so.[68] New organizations were set up in other countries to certify Fair Trade goods, such as the UK’s Fairtrade Foundation (1994).[69] In their first years, the Dutch and Swiss Max Havelaar organizations seem to have had budgets in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.[70]

In 1989, the International Federation of Alternative Trade (IFAT, later renamed the World Fair Trade Organization or WFTO) was set up in the Netherlands. It represented both producers in the Global South and retailers in the Global North, as well as various other supporting organizations.[71] Business scholar Matthew Anderson sees WFTO as supporting the “integrated supply chain route” to Fair Trade that is distinct from the “independent product certification route.”[72] WFTO later offered a “mark” which certifies an organization’s (rather than a product’s) compliance with Fair Trade values.[73]

The Network of European World Shops (NEWS!) was created in 1994.[74] The Fair Trade Federation was created the same year in North America to fulfill a similar role to the European Fair Trade Association.[75]

According to business scholar Alex Nicholls and Fair Trade marketer Charlotte Opal, in the mid-1990s, “a sales value ratio of 80 per cent crafts/textiles to 20 per cent food was the norm,” but cite a survey of the 11 constituent members of the European Fair Trade Association from 2001 finding that handicrafts had fallen to only 25% of sales value compared to 69% for food.[76] Perhaps exacerbating the rise of foodstuffs relative to handicrafts, Nicholls and Opal (2005) claim:

Fair Trade food positioned itself from the 1990s onwards as premium quality rather than ethically driven. Thus, it immediately appealed both to the multiple supermarkets and a broader customer base and could grow a new market quickly. Companies selling Fair Trade crafts and textiles (with the exception of People Tree, a Fair Trade clothing brand carried in Selfridge’s department stores) did not reposition themselves to address new markets, preferring instead to consolidate their position with ATOs and world shops. Secondly, the Fair Trade certification process is far better suited to commodity foods, such as coffee and tea, than to handicrafts or textiles. This is because the latter are far more diverse in terms of production techniques and specifications and it is, therefore, nearly impossible to devise and audit certification standards that can be broadly applied to them all… Consequently, crafts and textiles do not benefit from the marketing impact of a Fair Trade product logo.[77]

Cafédirect, the first Fair Trade brand of coffee, was established in 1991 in the UK by four UK ATOs (Oxfam, Traidcraft, Equal Exchange and Twin Trading) seeking to gain access to supermarket distribution.[78] Cafédirect’s founders mobilized supporters to encourage supermarkets to stock the products.[79] In 1991-2, mainstream UK retailers The Co-op, Safeway, and Sainsbury began to sell Fair Trade chocolates and coffee;[80] this process may also have been encouraged by Fair Trade advocates within the companies.[81] Similarly, NGOs were mobilized in a campaign to demonstrate sufficient demand for Divine Chocolate, another Fair Trade product.[82]

1997-present: The mainstreaming of Fair Trade

In 1997, Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International (FLO) was set up. The organization was intended to set international standards for Fair Trade products.[83] National labelling organizations like the UK’s Fairtrade Foundation, formed three years earlier, became members of FLO.[84]

In 1998, FLO, IFAT, NEWS! and EFTA started to collaborate explicitly. Collectively known as FINE (the first letter from each group’s name), they aimed to support their members to cooperate on campaigning, standards, and monitoring of Fair Trade.[85] FINE established an advocacy office in Brussels to influence European policymakers.[86]

Equal Exchange helped to launch the US labeling initiative, Transfair USA (now Fair Trade USA), in 1998.[87] From that point, activist groups sought to encourage US market adoption. Student groups successfully demanded that Fair Trade coffee be served on university campuses. Activist groups pressured Starbucks to sell Fair Trade certified coffee through demonstrations and threatening consumer boycotts. Fair Trade USA distanced itself from this activism, sending a softer message to consumers and businesses; since that time, it has used the slogan “every purchase matters,” and its leadership, staff, and board have tended to have business degrees and corporate experience.[88]

The activist campaign against Starbucks may have accelerated both the mainstreaming and loosening of Fair Trade standards. The Fair Trade seal was granted by Transfair USA to Starbucks in 2000, even though only 1% of the company’s coffee purchases met Fair Trade standards. This altered Transfair USA’s informal policy of not certifying organizations where less than 5% of their total sales met Fair Trade standards.[89] The proportion of Starbucks’ coffee purchases that were Fair Trade subsequently grew to over 10%.[90] Historian Matthias Schmelzer noted in a 2010 article that Starbucks alone accounted for 16% of global Fair Trade imports and 32% of US Fair Trade imports.[91] Subsequently, other major international chains have sought and received Fair Trade certification,[92] though the Fair Trade purchases of some of these chains, such as J. M. Smuckers, make up less than 1% of their total purchases.[93] Additionally, city councils in San Francisco, Berkeley, and Oakland agreed to buy Fair Trade brands after pressure from Global Exchange, one of the nonprofits that had campaigned against Starbucks.[94]

The number of Fair Trade certified commodities expanded from seven in 1998 to 18 by 2004. During the same period, the number of enrolled producer groups grew from 211 to 433 and sales of certified products rose from 28,902 to 125,595 metric tons.[95] This expansion meant that a greater proportion of workers for Fair Trade certified producers worked on plantations rather than small farms.[96] FLO imposed a temporary moratorium on certifying Latin American plantations and reviewed its labor standards; in 2005, this led to new “Hired Labour Standards” that improved workers’ training and strengthened workers’ organizations.[97]

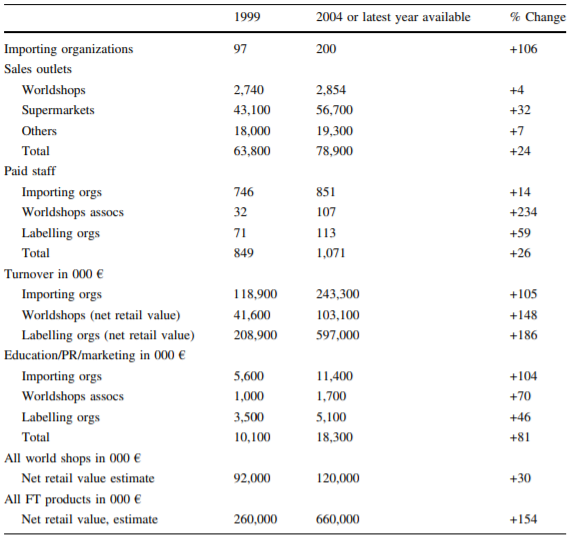

In the late 1990s to early 2000s, the number and resources of world shops continued to grow in Europe, though at a lower rate than supermarkets (see table 1).[98] Similarly, it seems that growth in Fair Trade foodstuff sales continued to outstrip growth in handicraft sales[99] and growth in sales of FLO-certified products outstripped growth in ATO turnover.[100]

Table 1: Fair Trade dynamics and resources in Europe in the early 2000s, from Wilkinson (2007).[101]

Business scholars William Low and Eileen Davenport provide anecdotal evidence that, between the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Fair Trade movement increased its emphasis on the idea of “sustainable development,” which incorporates concerns for the environment and for future generations.[102]

In several instances in the 1990s and 2000s, the European Parliament called on public institutions to use Fair Trade criteria in their purchase of goods and services and asked the European Commission to support this position. The Committee of the Regions and the European Economic and Social Committee have supported similar positions,[103] and various European politicians have publicly supported Fair Trade.[104] From 2001, numerous members of the US Congress also began to express support for Fair Trade.[105] Business experts Andy Redfern and Paul Snedker (2002) claim that, “[a]s a direct result of lobbying by ATOs, there is now a commitment from the EU to support trade development activities, including the promotion of Fair Trade.”[106] Indeed, all EU institutions came to buy and serve some Fair Trade coffee in this period and some also used Fair Trade tea.[107] However, the European Commission’s position has not been consistently positive, leading to difficulties for associated public institutions in procuring Fair Trade goods.[108]

Changes also occurred at the national level. For example,[109] from 1999, the French government sought to create a national legal framework for Fair Trade; a working group was created with this goal within the French Normalisation Association, including various French Fair Trade organizations and representatives from the French retail industry. By 2005, this effort had collapsed amid disagreements over the extent to which Fair Trade standards and ideals could be diluted. Instead, a non-binding information manual was published in 2005.[110] The French government also began using Fair Trade products in its public purchases. By 2009, this represented nearly one-third of the sales of Fair Trade products in France.[111]

The people of the town of Garstang in the UK voted almost unanimously for Garstang to become the world’s first Fair Trade town in April, 2000; the number of Fair Trade towns and regions in the UK grew to 77 by 2007, with 175 further applications pending.[112] Low and Davenport (2007) explain that, “[i]n order to become a fair-trade town/region, five goals must be met:

- The local council must pass a resolution supporting fair trade, and serve fair-trade coffee and tea at its meetings and in offices and canteens.

- A range of fair-trade products must be readily available in the area’s shops and served in local cafés and catering establishments (targets are set in relation to population). Fair-trade products must be used by a number of local workplaces (estate agents, hairdressers, etc.) and community organisations (churches, schools, etc.).

- The council must attract popular support for the campaign.

- A local fair-trade steering group must be convened to ensure continued commitment to fair-trade town status.”[113]

The Fair Trade towns initiatives institutionalize Fair Trade values, encouraging activism that focuses both on pressing the corporate sector to support Fair Trade and on influencing consumer behavior.[114] Various other public and nonprofit institutions have adopted ethical purchasing policies which include commitments to Fair Trade.[115]

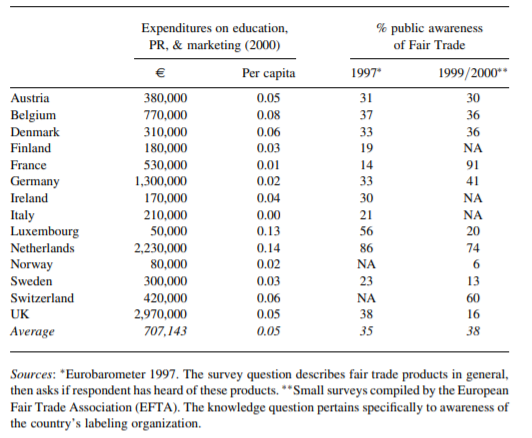

By the year 2000, the European national Fair Trade labelling organizations were spending hundreds of thousands or millions of Euros on marketing (see Table 2). Consumer awareness was quite high in some countries, but Fair Trade coffee beans (one of the movement’s most successful products) only represented about 3% of the market in The Netherlands, Luxembourg and Switzerland and around 1% in most other European countries.[116]

Table 2: Public awareness of Fair Trade in Europe, from Linton, Liou, and Shaw (2004)[117]

By comparison, Linton, Liou, and Shaw (2004) note that, “in 2001 TransFair USA spent US$486,202 on marketing and consumer education, or about $0.002 per capita. TransFair Canada spent CA$23,468, or about $0.001 per capita.”[118]

In the early 2000s, Fair Trade turnover increased nearly ninefold in France.[119] A poll conducted by IPSOS and Max Havelaar France found that public recognition of Fair Trade increased from 9% in 2000 to 81% in 2007[120] — consumer recognition seems to have at least doubled in the UK at this time.[121] French NGOs also underwent some reforms to professionalize and build capacity.[122] FLO-certified coffee substantially increased its market share in various countries between 2000 and 2007, including from 0.1% to 7% in France and 0.2% to 2% in the US; in the UK, FLO-certified coffee rose from 1.5% of the market in 2000 to 20% in 2004.[123]

In 2001, following recommendations by McKinsey consultants, Oxfam decided to shut down its ATO[124] and focus more on advocacy and political campaigning,[125] though it subsequently launched Progreso cafés, which partnered with three coffee co-operatives in Honduras, Ethiopia and Indonesia, sold only Fair Trade coffee, and explicitly promoted Fair Trade.[126] In the early 2000s, Cafédirect (a UK-based ATO) shifted to a more mainstream, product-centered marketing strategy, moving away from their former emphasis on the intended beneficiaries;[127] Nicholls and Opal argue that this was part of a broader marketing shift in the movement at this time to achieve more mainstream consumer success.[128] Other ATOs also seem to have shifted their distribution methods and adopted more conventional business strategies at around this time.[129]

The International Social and Environmental Accreditation and Labelling Alliance was founded in 2002 by FLO and various accreditation labelling organizations from beyond the Fair Trade movement.[130] Its stated mission is to “strengthen sustainability standards systems for the benefit of people and the environment,”[131] though political scientist Gavin Fridell describes its “primary goal” as “to gain credibility in the eyes of international trade bodies and demonstrate that its members’ initiatives do not pose a barrier to free trade and neoliberal restructuring.”[132]

In 2002, the first FLO certification for an industrial product — sports balls — was launched, despite some criticism of the standards from within the Fair Trade movement and from labor rights activists.[133]

On May 4, 2002, the first World Fair Trade Day was celebrated; this is now an annual occurrence.[134] The movement has also promoted “Fair Trade months” and other promotional periods.[135]

The 2004 UN Conference on Trade and Development included a symposium on Fair Trade, with nearly 200 attendees in the morning policy session, including many government officials. [136] According to Nicholls and Opal, This event resulted in the São Paulo Fair Trade Declaration that, “actively challenged UNCTAD to support the management of world commodity markets and foster greater trade price stability and fairness… The declaration was signed by more than 90 Fair Trade organizations from 30 countries, was entered into the UNCTAD record, and was also hand-delivered to UN Secretary General Kofi Annan.”[137]

In 2004, Cafédirect launched its initial public offering[138]; this seems to have been the first IPO on the stock market for a Fair Trade company.[139] In the same year, Nestlé, Sara Lee, Kraft, and Tchibo signed a “Common Code for the Coffee Community” to improve conditions on coffee farms.[140]

In 2005, Media, Pennsylvania became the first Fair Trade Town in the US. Two years later, Fair Trade USA, Lutheran World Relief, and Oxfam America jointly funded a website, coordinating staff and organizing toolkits for a broader Fair Trade Towns USA initiative.[141] This initiative does not seem to have been as successful in the US as in some European countries, however; the Fair Trade Towns International website lists 2,030 Fair Trade Towns in 34 countries, 45 of which are in the US, with the number per country ranging between one (eight countries) and 687 (Germany).[142]

In 2005, the Network of European World Shops (NEWS!) was integrated into the World Fair Trade Organization.[143] The WFTO’s income was around €0.9 million in both 2008 and 2018,[144] compared to €6.4 million and €21.4 million for FLO in those two years.[145] This is suggestive of the decline of the importance of world shops and the integrated supply chain approach to Fair Trade relative to certification of products sold in mainstream retail outlets.

In 2010, the International Labour Rights Forum published a report documenting the failure of FLO certified soccer ball factories to pay minimum wages, as well as their use of child labor. FLO posted a response on the public relations-focused “Latest News” section of its website and substantially increased the number of its articles that discussed labor issues.[146] In the same year, FLO established a Workers’ Rights Advisory Council, and in 2012, FLO’s board voted unanimously to adopt the Council’s “New Workers’ Rights Strategy.”[147]

In September 2011, Fair Trade USA separated from FLO, seemingly because Fair Trade USA sought to use a lower standard for Fair Trade certification and increase its appeal to mainstream US businesses.[148] At that time, its certified products are estimated to have represented 90% of the US Fair Trade market.[149] The decision has been criticized by FLO and the WFTO, as well as Equal Exchange (who published a full page advertisement in the Burlington (VT) Free Press encouraging the multi-billion dollar corporation GMCR to withdraw its support for Fair Trade USA and circulated a petition in support of “authentic fair trade”[150]) and various other US Fair Trade organizations.[151] Given that Fairtrade America have continued to offer FLO-certified products[152] but Fair Trade USA’s certification no longer meets FLO standards, the split has contributed to an increase in the number of competing Fair Trade labels with slightly different visions that are offered to US consumers; the four now available are Fair Trade USA, Fairtrade America, Fair for Life, and the Small Producer Symbol.[153] Numerous producers and mainstream retailers have continued to support Fair Trade USA; over 100 have signed on as supporters of its Fair Trade for All initiative, for example.[154] Despite the split, sales of Fair Trade USA[155] and FLO-certified products have continued to grow; the US retail sales value of products that meet FLO’s criteria had nearly reached $1 million by 2017, close to the retail sales value before the split.[156] Since the departure of Fair Trade USA (which had long advocated a more mainstream approach to certification[157]), FLO has, for the first time, given as many board seats to producers as to national labelling initiatives.[158]

In 2013, members of the WFTO approved a new Guarantee System for Fair Trade verification.[159] In 2014, FLO adopted a revised Standard for Hired Labor.[160]

FLO’s 2016 global strategy document outlined a plan to build a “truly global support base for Fairtrade” by 2020, “putting products on ever more shelves across the world” and prioritizing “growth in Brazil and India.”[161]

The Extent of the Success of the Fair Trade Movement

Changes to Behavior

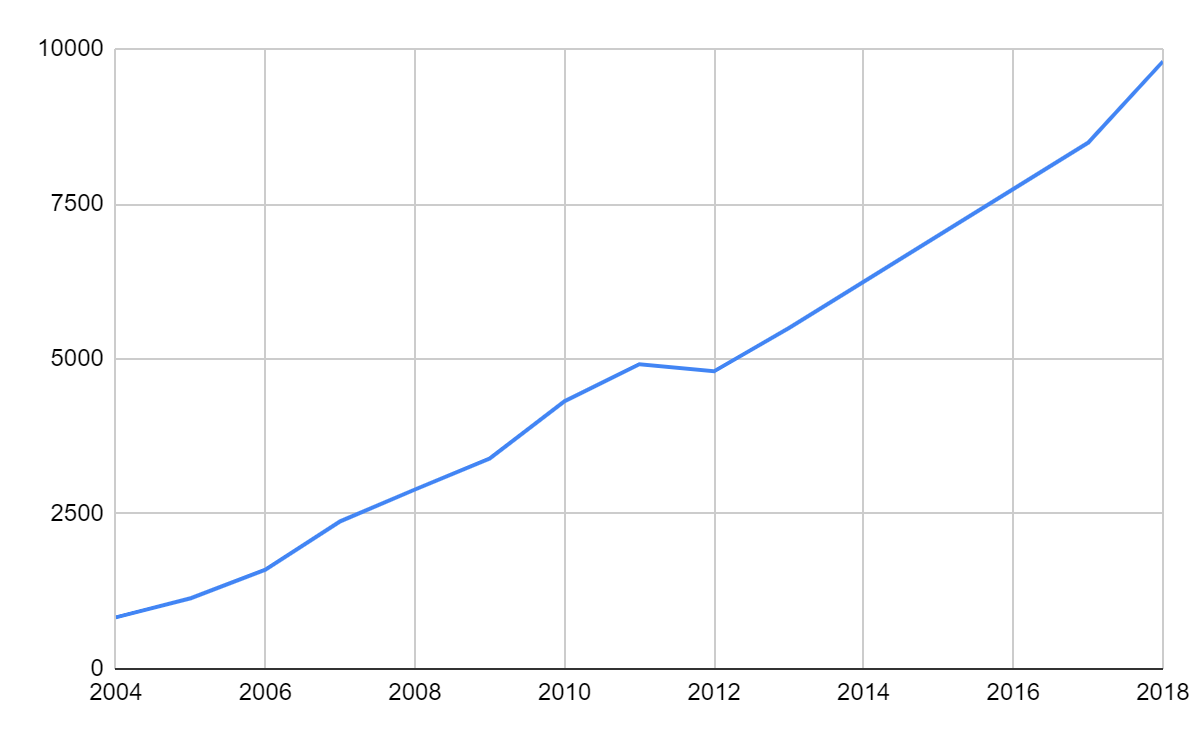

Global retail sales of FLO-certified Fair Trade products have increased from €0.8 billion in 2004 to €9.8 billion in 2018 (see figure 1 below). There is little evidence of the growth rates declining, even when the data is analyzed within the major product types or countries. The main exception is the United Kingdom, where retail sales grew roughly tenfold from 2004 to 2013 (from €206 million to €2.045 billion) but have stagnated since then (€2.014 billion in 2017).[162] Additionally, the total weight of FLO-certified Fair Trade products sold (as opposed to their total retail value) appears to have plateaued in 2018 and 2019.[163] If non-certified Fair Trade goods (e.g. handicrafts not amenable to certification) were counted, all these figures would be slightly higher.[164]

Although Fair Trade products have captured substantial market share for some product types in some countries,[165] the €9.8 billion retail sales value of Fair Trade products in 2018 represents less than 1% of the value of international trade in that year.[166] It would be premature to say that the Fair Trade movement has failed, since it may continue to grow. However, it does not yet seem to have gone very far towards achieving its ultimate goals.[167]

Figure 1: Total Fair Trade retail sales (€ millions), by date, according to FLO[168]

Factors which prevent further expansion of Fair Trade include:

- The perceived low quality of some Fair Trade goods.[169]

- Insufficient consumer demand in the Global North, which prevents the expansion of involvement in schemes in the Global South.[170] Some major companies have bought substantial amounts of Fair Trade coffee but then been unable to sell it.[171]

- The alternative, lower quality Fair Trade initiatives set up by some Northern retailers.[172]

- The direct marketing and labelling initiatives by some Southern producers that undermine international Fair Trade initiatives by undercutting prices while providing lower standards.[173]

- A lack of awareness and understanding among Northern consumers,[174] perhaps due partly to a “decentralized and unstrategic” branding process.[175]

- A lack of awareness and understanding among Southern producers, which may reduce their long-term commitment to the schemes.[176]

- A preference among some Northern activists and consumers for supporting local producers over premium for foreign Fair Trade products.[177]

- The slow and expensive standards setting process; Redfern and Snedker (2002) noted that there were only “seven product categories with agreed standards [after] 13 years” of FLO certification.[178]

- The burden that the Fair Trade standards require of the producers themselves.[179]

- The high standards and demands that make involvement less attractive to mainstream retailers.[180]

Fridell hypothesizes that the greater success of Fair Trade in Europe than North America may be partly due to historical cultural factors and partly due to FLO and Fair Trade mainstreaming having been initiated in Europe.[181]

Benefits to the Intended Beneficiaries of the Movement, Assuming Changes to Behavior[182]

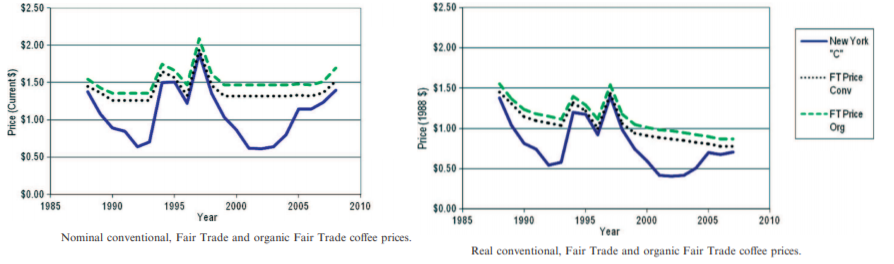

As long as the Fair Trade floor price is above the market price (see, for example, figure 2 below), participating producers receive a higher price for their produce. They are also paid an additional Fair Trade “premium” and tend to be given long-term contracts.[183] Nicholls and Opal (2005) summarize other intended benefits for producers: “Transparent and long-term trading partnerships… Co-operative, not competitive, dealings… Provision of credit when requested… Provision of market information.”[184]

Figure 2: Fair Trade coffee prices compared to conventional coffee prices, 1985-2010, from Bacon (2010).[185]

There has been some empirical research into these intended benefits. For example:

- Surveys find that Fair Trade–certified coffee producers receive higher prices than conventional farmers,[186] though Bacon (2010) found that, “Fair Trade minimum [coffee] prices lost 41 percent of their real value from 1988 to 2008” (see Figure 2).[187]

- A number of case studies find evidence that participating producers have superior economic and social conditions.[188] There is some evidence from interviews and statistical analysis of the sales data of certified and non-certified producers that Fair Trade participation causes these improvements.[189]

- Economic modelling by Robbert Maseland and Albert De Vaal (2002) suggests that, at least in the short-run, Fair Trade is only sometimes better for producers than free trade; this depends on variables such as the goods traded and transportation costs.[190]

- Using data from FLO’s annual report, we can estimate that less than 10% of the price markup paid by consumers was actually received in “Fairtrade Premium” payouts by farmers and workers in 2018.[191] This estimate does not account for any of Fair Trade’s other benefits, including financial benefits from the minimum price guarantee. Some previous estimates by other researchers have been similar, even when accounting for the price guarantee, though the evidence is mixed.[192] Accounting for positive indirect effects makes the efficiency of Fair Trade certified products in terms of transferring money from Northern consumers to Southern consumers seem better.[193]

A number of other effects on producers have been hypothesized and researched. For example:

- There is evidence that some producers have become dependent on ATOs.[194]

- By interfering with free market mechanisms, Fair Trade might hinder economic growth in the Global South.[195]

- There seem to be some positive effects of Fair Trade on gender equity among producers.[196]

- Fair Trade may bring educational and psychological benefits to partnering communities and help to preserve indigenous culture.[197]

- Fair Trade may encourage greater representation for workers relative to owners and for cooperatives relative to plantations.[198]

- Some scholars have argued that some Fair Trade marketing actually reinforces the sense of superiority of Northern consumers over Southern producers.[199]

- Some Fair Trade requirements, such as prohibitions on child labor and genetically modified crops, seem to reflect the preferences of consumers in the Global North rather than the best interests (or at least autonomy) of Southern producers.[200]

- Fair Trade may have substantial negative effects on non-participating producers.[201]

- Even if it has a positive effect on participating producers, Fair Trade often seems to have no positive effect on wage laborers employed by these producers.[202]

Legislative and Legal Changes

Despite buying some Fair Trade products and making pronouncements in support of the ideals,[203] international institutions (such as the European Commission and World Bank) and Northern national governments have continued to implement various neoliberal and free trade policies[204] or use tariffs that harm producers in the Global South.[205]

Nevertheless, the introduction of ethical purchasing policies by political and public service institutions is not trivial, since they make up a large proportion of total consumption[206] and seem likely to affect broader social norms.

Acceptance and Inclusion

There have been various favorable statements by politicians.[207] The government institutions in the United Kingdom have demonstrated relatively strong acceptance and inclusion of Fair Trade organizations and their goals:

- Traidcraft and other Fair Trade organizations were consulted by the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID, set up in 1997[208]) for its early policies and white papers.[209] DFID seems to have remained supportive of the ideals of Fair Trade and continued to seek input from Fair Trade organizations.[210] However, despite the objections of Fair Trade organizations,[211] DFID has now merged with the UK foreign office.[212]

- The UK government funds the Fairtrade Foundation and provides procurement contracts.[213] DFID provided £1.9 million in grants to support the work of the Fairtrade Foundation between 1999 and 2008.[214]

- Municipal governments provide some support for Fairtrade School and Fairtrade Town programs.[215]

- The Scottish Parliament and the UK House of Commons buy and serve some Fair Trade coffee.[216]

Various companies have also expressed support for the goals of Fair Trade.[217] Some major coffee companies have attempted to resist legitimating the Fair Trade movement and its goals,[218] though some have also purchased Fair Trade raw materials.[219]

Overall, the movement seems at risk of co-option — securing acceptance, inclusion, and rhetorical support, despite only securing limited benefits for its intended beneficiaries (see “Changes to Behavior” above).[220]

Changes to Public Opinion and the Salience of the Issue

Although difficult to measure and quantify, the growth of the Fair Trade movement has likely encouraged a social norm of considering the needs of geographically distant human beings and a wider norm of “corporate social responsibility.”[221] For example, DFID’s 2002 survey found that 73% of UK consumers were “concerned” about poverty in the developing world and 69% saw this poverty as a moral issue.[222] It is unclear, however, to what extent these views have been influenced by the Fair Trade movement. Fair Trade USA claims that “consumer awareness” had reached 60% by 2018.[223] Certainly, Fair Trade has become widely recognized in many countries in the Global North (e.g., see Table 2). YouGov found that, in the UK, 89% “have heard of” The Fairtrade Foundation, 65% have a “positive opinion” of the organization, and only 5% have a “negative opinion” of it, the Fairtrade Foundation “the 39th most popular charity & organisation and the 32nd most famous” in the UK.[224] Various surveys have been conducted that show overall support for Fair Trade.[225]

Sociologist Kathryn Wheeler, examining data from several iterations of the UK Centre for National Statistics’ Omnibus Survey in 2002, found that 35% of respondents selected “Buying fair-trade goods” as first or second when asked: “In which ways, if any, do you think you as an individual can most effectively contribute to reducing poverty in developing countries?” and provided with a list of ten options.[226] This was the second most popular option, beneath “Donating to charities or other appeals on behalf of developing countries” (56%) but above “Putting pressure on politicians to increase the assistance which the Government gives to developing countries” (23%).[227] The proportion choosing fair-trade first or second increased yearly to 45% in 2005; in 2007 and 2008, buying Fair Trade overtook donating to charity as the most popular response.[228]

In general, however, there is relatively little polling explicitly about opinion on Fair Trade, its importance, or the movement’s goals.[229]

Provider Availability

Fair Trade products are sold in tens of thousands of outlets (see Table 1). FLO provides the following statistics for involvement in Fair Trade in 2019[230]:

- 1,822 Fairtrade-certified producer organizations,

- 1.7 million farmers and workers in 72 countries,

- More than 2,785 companies have licensed more than 35,000 Fairtrade products worldwide.

Currently, these numbers represent very small percentages of the potential providers and beneficiaries, globally,[231] though they may continue to grow.

Organizational Resources

FLO’s income was €21.4 million in 2018;[232] Fair Trade USA’s income was $19.2 million and the UK’s Fairtrade Foundation’s income was £12.2 million in the same year.[233] FLO lists 21 affiliated National Fairtrade Organizations[234] and the UK is, by quite some distance, the country with the highest value of annual Fair Trade retail sales.[235] Hence, it seems likely that the total resources dedicated to Fair Trade nonprofits each year does not currently substantially exceed $100 million.[236] This figure would presumably be much higher if resources from involved for-profit organizations (ATOs or mainstream retailers like Starbucks) were also counted.

Features of the Fair Trade Movement

Intended Beneficiaries of the Movement

- Producers in the Global South are excluded from humanity’s moral circle in the sense that they do not have access to the same rights, welfare, or standard of living afforded to other humans,[237] and international trading practices do not necessarily prioritize the wellbeing of producers in the Global South.[238]

- Policy and consumption-related decisions in the Global North are mostly made by people who live (and whose recent ancestors lived) there[239] rather than by producers in the Global South, indicating that the movement’s intended beneficiaries are limited in their ability to participate in it.

- The number of direct intended beneficiaries of the Fair Trade movement is larger than some movements encouraging moral circle expansion (e.g., the prisoners’ rights movement) but smaller than others (e.g., the farmed animal movement).[240]

- ATOs often work closely with Southern producers.[241] Some Fair Trade standards and strategies have been designed by Northern buyers, retailers, and activists in collaboration with Southern producers.[242] Others have not included Southern producers in the design, however,[243] and mainstream Fair Trade is sometimes criticized for having insufficient involvement from its intended beneficiaries.[244]

- Fair Trade products sometimes promote personal narratives about the producers of the products, which may help to drive sales and activist motivation.[245]

Institution

- The institution targeted by Fair Trade is the system of international trade and economic relations between countries.[246] Debate around Fair Trade is often integrated into wider debates about economic systems.[247]

- The “fairness” of trade is relative. This means that declining standards are a more serious concern than for some other consumer movements.[248] Similarly, it is possible for consumers to seek to shift more of their consumption towards Fair Trade certified products without firmly committing to consuming only certified products.[249]

Advocacy

- The Fair Trade movement has sought to build awareness of Fair Trade among consumers and encourage them to buy Fair Trade products. Fair Trade marketers have utilized celebrity support,[250] run promotional campaigns,[251] sought coverage in mainstream media,[252] and reached out to students and activists.[253]

- The Fair Trade movement has also targeted businesses, encouraging them to pledge to sell Fair Trade products.[254] In some cases, it has prioritized companies already favorable to socially responsible practices.[255]

- There seem to have been few instances of confrontational corporate campaigns against businesses.[256]

- Student activists have sought to encourage university campuses to procure Fair Trade products.[257] National nonprofits provide some support for this activism.[258]

- There have been limited efforts by the Fair Trade movement to lobby or pressure governments and international institutions to improve international trading systems.[259] There has been some continued pressure for international reform in this manner from Southern governments and NGOs.[260]

- Some supporters of the Fair Trade movement are more interested in broad social and economic change — such as providing an “alternative to the dominant paradigm of international free trade and the hegemony of transnational capital” — than they are in providing direct support for producers in the Global South.[261] Nevertheless, a study of framing used by the Fair Trade movement in print media and radio found that only 1% of comments used anti-capitalist framing.[262]

- Though some efforts at movement-wide coordination, such as the development of FLO, have been given substantial funding,[263] various other efforts have received little support.[264]

- Fair Trade companies and Fair Trade nonprofits may draw on a similar pool of job candidates who are highly supportive of the movement’s goals.[265]

- In addition to the founding role of Christian groups in ATOs, world shops,[266] and Fair Trade nonprofits,[267] religious networks have continued to be mobilized for Fair Trade advocacy, though they do not seem to have dominated the movement.[268]

- The Fair Trade movement has broadly attempted to improve the world in various ways rather than focusing exclusively on a single set of intended beneficiaries. There has been some overlap between the Fair Trade movement and the environmental movement.[269] FLO encourages organic certification[270] and, for a while, FLO considered only cooperatives that already had organic certification for Fair Trade certification.[271] However, environmentalism has not been a high priority for the Fair Trade movement.[272] The Fair Trade movement has also included some emphasis on improving gender equality[273] and banning child labor,[274] even though these efforts are not necessarily core to the goal of “offering better trading conditions to, and securing the rights of, marginalized producers and workers.”[275]

Society

- People in the Global North likely grant more consideration to geographically distant human beings than they do to other groups of sentient beings that are excluded entirely or partly from the moral circle. For example, a study that asked participants to rate 30 different entities by the “moral standing” that they deserved found that “outgroup” members (a foreign citizen, a member of an opposing political party, and somebody with different religious beliefs) were deemed by participants to deserve more moral standing than animals, the environment, or villains, but less than stigmatized individuals (a homosexual, a mentally challenged individual, or a refugee), ingroup members, or family and friends.[276]

- Concerns about global injustice and strong identification “with all humanity” are associated with the consumption of Fair Trade products.[277]

- The consumers of Fair Trade goods tend to be fairly privileged.[278] This tendency may have been reinforced by targeted Fair Trade marketing.[279]

- Female consumers seem to be slightly more aware of, optimistic about, and likely to buy Fair Trade products than male consumers.[280]

- A 2011 US survey found that Buddhists and Hindus reported being more likely than nonreligious people to buy Fair Trade, while Jews, Protestants, Catholics, and other Christians reported being less likely to do so.[281] Those indicating that religion influenced how they consumed were more likely to report buying Fair Trade products.[282] Interviews by sociologist Kathryn Wheeler suggest that some see their consumption of Fair Trade products as part of their efforts to be good Christians and come to participate in the movement via “faith-based networks.”[283]

- Wheeler’s interviews suggest that, for some consumers, Fair Trade constitutes “an alternative culture which allows its participants to attach meaning to their everyday actions and ways of life.”[284]

Strategic Implications

Consumer Action and Individual Behavioral Change

- Engaging directly with mainstream market institutions and dynamics will enable a social movement to influence consumer behavior much more rapidly than efforts to build “alternative” supply chains.

There does not seem to be clear sales data for the Fair Trade movement in its early years. However, scholars often claim that the movement’s growth was beginning to stagnate in the 1980s.[285] By contrast, FLO’s data on international sales since their founding in 1997 suggests steady growth.[286] We could hypothesize that this renewed success might have been encouraged by indirect, exogenous factors such as continued economic growth in the Global North permitting more spending on “ethical” products,[287] or a more general expansion of the moral circle. The rise in ethical consumerism[288] and developments in other movements, such as the environmental movement and anti-death penalty movement,[289] at around this time provide some evidence for this.

However, intuitively, this renewed success seems likely to have been caused, at least in part, by the introduction of Fair Trade certification schemes combined with the shift from handicrafts to foodstuffs and from “alternative” trade to a mainstream “fair” trade commercial strategy. Some of the movement’s later successes, such as the partial switch to Fair Trade-certified products by multinational corporations like Starbucks,[290] presumably could not have occurred without certified foodstuffs. At the least, the sale of certified foodstuffs expanded the Fair Trade movement’s reach into new product categories, such as coffee.[291]

Several chronological and geographical comparisons also provide evidence that the change in strategy played an important role in the movement’s renewed success:

- The movement was still focusing on “alternative” trade in handicrafts in the 1980s, when it began to stagnate.[292] By the late 1990s, the movement had switched towards foodstuffs, product certification, and mainstream distribution.[293]

- Handicrafts fell from roughly 80% of Fair Trade sales value in the mid-1990s to roughly 25% in 2001.[294] This trend seems to have continued after 2001.[295] Additionally, the number and resources of supermarkets selling Fair Trade grew faster than the number and resources of world shops (see table 1), and growth in sales of FLO-certified products outstripped growth in ATO turnover.[296]

- Marketing scholars Bob Doherty, Iain A. Davies, and Sophi Tranchell argue that there was more rapid growth of Fair Trade in the UK, which adopted a more mainstream approach than Italy, which prioritized the “alternative” and solidarity aspects of Fair Trade; France adopted a more moderate mainstreaming strategy and experienced moderate growth.[297]

At least some consumers purchase Fair Trade products without being aware that they are doing so;[298] accidental purchases would presumably be less frequent without mainstream distribution. Occasionally, mainstream partners may actively promote relevant products and ideals, too.[299]

- Engaging directly with mainstream market institutions and dynamics may lead to co-option and a lowering of standards.

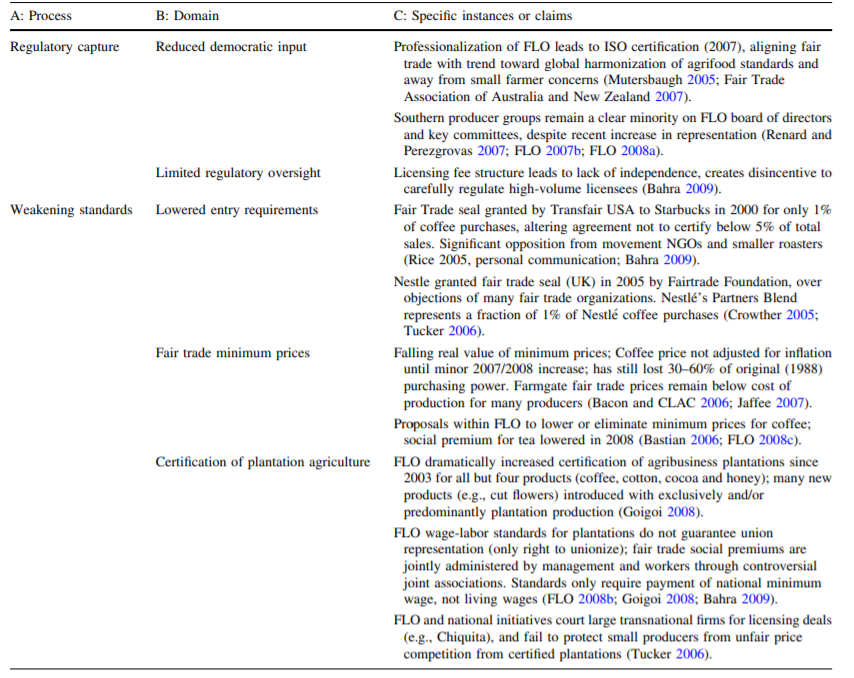

There has been a lowering of standards for various Fair Trade programs (see Table 3) which has been associated with the involvement of plantations and mainstream companies in Fair Trade.

Table 3: “Cooptation in fair trade,” from Jaffee and Howard (2010).[300]

Additionally, Low and Davenport (2006) provide examples of the Body Shop, Nestlé, and

Ahold Delhaize seeming to use terminology and ideas similar to the Fair Trade movement, but without “the oppositional and transformative elements that call for root and branch restructuring of international trading regimes.”[301] Some companies have also set up alternative, lower quality Fair Trade initiatives (sometimes alongside purchasing small amounts of Fair Trade certified products).[302] Several companies have signed onto the Sustainable Agricultural Initiative, which offers weak protections for laborers,[303] or used the Rainforest Alliance certification scheme, which includes wage and working conditions standards (amongst other requirements focused on environmental goals[304]) but lacks minimum price requirements.[305] (Indeed, sales of Rainforest Alliance certified products have overtaken sales of Fair Trade certified products.[306]) These actions could be seen as mainstream retailers autonomously driving further momentum for the Fair Trade mission,[307] though sometimes partial steps by mainstream retailers towards Fair Trade’s goals have been coupled with a public critique of the movement.[308]

This process of co-option may have been encouraged by financial incentives at the participating companies (who can use certification as a marketing tool)[309] and at the certifying organizations themselves (who receive license fees for certifying products).[310] Despite the pressures from private sector businesses, a study of the movement’s representation in mainstream media from 1997 to 2007 suggests that Fair Trade continued to be represented as being primarily about “decommodification” and “fair exchange” rather than just creating a “warm glow” for consumers.[311]

There has been substantial debate within the movement[312] and among academics[313] about whether the introduction of Fair Trade certification schemes, combined with the shift from handicrafts to foodstuffs and from “alternative” trade to a mainstream “fair” trade commercial strategy, were positive overall for the movement’s intended beneficiaries. In the short-term, given the size of the increase in Fair Trade sales (see the strategic implication above), it seems likely that this mainstream adoption has helped producers in the Global South. The longer-term consequences are much less clear. In addition to the concerns about co-option and lowering of standards, some worry that mainstream companies might not protect Fair Trade ideals and supply chains if consumers lose interest or economic conditions become less favorable.[314]

Several researchers note that a similar process of co-option and weakening standards has occurred in the organic movement.[315] In that movement, the USDA and US Congress have been involved in setting relatively low standards, such as preventing organic certifiers from enforcing stricter standards than the USDA’s requirements.[316]

- Social movements should implement strategies to resist pressure from private sector businesses to weaken the standards of certified products.

Daniel Jaffee and Philip H. Howard (2010), after examining the evidence of co-option in the Fair Trade and organics movements, argue that, “alternative agrifood initiatives, particularly those based on certification,” should:

- Carefully monitor and manage market growth,

- “[D]esign explicit barriers within their rules and standards that simply prevent the entry of big players” that might lower standards,

- Design “the structure of governance institutions” so that proponents of the movement are “guaranteed sufficient ongoing representation to ensure that their core principles remain in control.”

- Possibly “steer clear of state-based standards,” although non-state standards are also subject to downward pressure.[317]

A number of other tactics that could plausibly reduce the risks of mainstream engagement have been suggested by scholars of Fair Trade. These include:

- An increase in boycotts and other “naming and shaming” corporate campaign tactics (the ‘stick’) alongside certification schemes (the ‘carrot’).[318]

- Internationally “solidifying the certification process in order to achieve a universal public standard.”[319]

- Seeking state recognition and institutionalization of the criteria for Fair Trade certification.[320]

Minimizing the number of competing certification schemes and offering binary (e.g., vegan or not) rather than relative (e.g., more or less high welfare) certification schemes also seem likely to help resist downward pressure (see below).

- Social movements should seek to minimize the number of competing certification schemes.

Confusingly, the Fair Trade movement has multiple competing standards and certification bodies.[321] Additionally, some products may be candidates for certification on multiple different ethical or sustainability issues, such as Fair Trade, organic, and shade-grown standards for coffee.[322] These different certification schemes could signify vastly different standards and impacts, yet companies can use the various schemes interchangeably, offering a variety of products to consumers without seeking to promote particular standards more universally within their supply chain.[323] Given that many consumers do not understand the complex motivations behind Fair Trade,[324] they’re unlikely to be able to assess the extent to which different certification schemes successfully achieve those goals.

Consider by analogy that the public seems to vastly underestimate the differences in cost-effectiveness between different charities.[325] Hence, companies have little incentive to adopt high standards if they can gain similar amounts of ethical credibility by adopting a low standard and using comparable labelling and marketing.[326] Indeed, some of the largest purchasers and retailers of coffee have taken a variety of initiatives to address the concerns of the Fair Trade movement without adopting Fair Trade standards or buying much Fair Trade certified coffee.[327] Despite this complexity, the use of a relatively common, shared logo has been seen as a strength of the Fair Trade movement when compared to the organics movement.[328]

Offering as few certification schemes as possible will presumably therefore help to reduce consumer confusion and opportunities for companies to lower standards while receiving similar marketing benefits. This suggestion seems consistent with standard economic theory: since mainstream companies act as the consumers of product certification schemes given that they use the schemes as marketing devices, we should expect competition among certification schemes to benefit mainstream companies. Social movements should be seeking good deals for their intended beneficiaries, not.

- Relative, flexible certifications may be especially susceptible to downward pressure.

The Fair Trade movement has faced downward pressure on standards from its mainstream corporate stakeholders.[329] All else equal, it may be preferable for social movements to focus on binary rather than relative certification schemes, since these may be more easily defensible against industry pressure. For example, the farmed animal movement could focus efforts on the certification of products as free from animal ingredients, rather than the certification of products as high welfare. On the other hand, sociologist Curtis Child has compared the Fair Trade movement to the movement for socially responsible investing and hypothesized that Fair Trade’s more “concrete” (binary) industry-wide standards have given it a more “polarizing quality,” creating a “cleavage point around which coalitions [of opposition] are built.”[330]

- International standards may be seen as more credible than local or national standards.

Economists Arnab K. Basu and Robert L. Hicks (2008) found through choice experiments and econometric modelling that, “in both the US and Germany, the FLO had the strongest effect [on willingness to pay for Fair Trade coffee] relative to the in-country certifying agency and local growers associations.”[331] The reasons for this discrepancy are not explored in their paper. This could be explained by differing levels of credibility between international and national certification bodies or just by differing levels of brand recognition.

- Certification schemes may be ineffective or counterproductive in high-priority countries.

Evidence suggests that Fair Trade does not help producers in the poorest countries and “may be diverting at least some demand from poor to better-off countries whose producers have a better capacity to organise and pay the relevant fees.”[332] Comparably, sociologist Peter Leigh Taylor (2005) analyzes forest certification and labelling schemes, noting that, “in practice, market mechanisms currently appear to encourage concentration of forest certification in Northern temperate and boreal forests, rather than in the tropical forests certification originally aimed to protect.”[333] In this sense, it seems that certification schemes provide most assistance to those suppliers who can deal with the “significant obstacles to success with certification.”[334] Arguably the farmed animal movement also needs to prioritize its efforts towards the Global South because of the large numbers of farmed animals there,[335] but the Fair Trade movement’s experience serves as a reminder that relatively poor producers in the Global South may find it more difficult to meet welfare requirements, so the certification schemes may struggle to reach a critical mass of engagement.

- Certification schemes risk driving up the price of ethical products.

Certification schemes can involve more expensive production or supply chain processes, such as the minimum price that must be paid to the producers of Fair Trade certified products, and the payment of the Fair Trade Premium.[336] The certification process itself also involves costs for participating businesses.[337] Although these businesses may shoulder some of these costs themselves, they may pass costs onto consumers in order to maintain profits. Additionally, private sector businesses may use certified products to “identify price-insensitive consumers who are willing to pay more,” adding price premiums that increase their own profit margin without further benefits for the intended beneficiaries of the certification scheme.[338]

- Price, quality, and the benefits accrued to the intended beneficiaries all seem to affect consumer demand and willingness to pay.

A meta-analysis of over 80 research papers testing willingness to pay for socially responsible products that benefit people, animals, or the environment found that “the mean percentage premium” that people are willing to pay for these products is 16.8% and that, “on average, 60% of respondents are willing to pay a positive premium” for them.[339]

Basu and Hicks (2008) found through choice experiments and econometric modelling that higher prices had significant, negative effects on willingness to purchase Fair Trade coffee and that grower revenue from the products had significant, positive effects.[340] Subsequent surveys and experiments provide evidence that consumers are willing to pay more for Fair Trade products but are still somewhat sensitive to price changes, especially for lower-quality products,[341] and will often still buy less ethical products that excel on other attributes.[342] A small survey of 14 businesses in Seattle also found that respondents believed that price was an important factor, though businesses expected that quality and consumers’ “Social Consciousness” were stronger predictors of Fair Trade demand.[343] Sociologist Kathryn Wheeler summarizes from interviews with UK Fair Trade consumers that, “[c]ompeting ethical labels, family concerns, price and quality were all factors that made Fairtrade options less appealing.”[344] Focus groups have suggested that price, quality, and value are more important in affecting consumer demand than a company’s ethical behavior, though this latter factor still affects willingness to pay.[345]

- Marketing efforts likely increase awareness and purchases of certified products, but high awareness and support do not necessarily lead to widespread changes in consumer behavior.

Linton, Liou, and Shaw (2004) analyzed data from a 1997 Eurobarometer survey that “describes fair trade products in general, then asks if [the] respondent has heard of these products.” They found through logistic regression that, after controlling for an individual’s income, age, gender, and political leanings, “the odds of knowing about Fair Trade increase with the time that a labeling organization has existed in one’s country of residence” by 10% per year. Using the same survey, the authors conducted a “logistic regression of buying Fair Trade products (given that one knows about them)” and found that “the odds of buying increase by 8% per year of [a national labelling organization’s] presence in one’s country.”[346]

These regressions do not account for differing amounts of spending per capita on Fair Trade marketing, though the authors note that this ranges from less than 0.01 Euros to 0.14 Euros. The authors also ran regressions that include an additional variable signifying residence in The Netherlands; this was the strongest predictor of awareness (odds ratio 9.37) and of buying Fair Trade products, given that one knows about them (OR 1.63). The authors note that, “Max Havelaar Netherlands and TransFair-Minka Luxembourg spend about twice as much as other European labeling organizations on education and promotion,” which may explain why residence in the Netherlands is such a strong predictor of awareness and consumption of Fair Trade products.[347] They list several other possible contributing factors: the longer history of the movement in the country, the greater apparent availability of certified products in mainstream retailers, and the wide variety of certified product types.[348]

Of course, there are limits to the achievements that marketing alone can yield.[349] An experiment with German students provides mixed evidence about whether knowledge of Fair Trade increases consumers’ willingness to pay.[350] High theoretical support from consumers for Fair Trade[351] and high consumer awareness[352] have not translated into high market share for Fair Trade products.

- Individuals who participate in consumer action are more likely to participate in other forms of activism.

Political scientists Dietlind Stolle, Marc Hooghe, and Michele Micheletti (2005) conducted a survey of 1,015 students in Canada, Belgium, and Sweden. They created a scale that measured participation in political consumerism (e.g., boycotting products. Scores on this scale did not have significant negative associations with any of the “conventional” political participation methods that they asked about: student voting, political party participation, contacting politicians or organizations, or appearing on media. There was also no significant positive association with the overall measures of “conventional participation” or “individualistic participation” (e.g., “[s]igning petitions, wearing T-shirts”). However, there was a significant positive association with a combined measure for other forms of “unconventional participation” — “[d]emonstration, culture jamming, internet campaign, civil disobedience, globalization advocacy.”[353]

Stolle, Hooghe, and Micheletti also analyzed the results of a previous international survey series showing that fewer than 5% of respondents had been involved in boycotts in 1974 and that this rose to above 15% by 1999; involvement in other forms of political activity (petition signing, demonstrations, and building occupation) also grew during that period, albeit at lower rates.[354]

Political scientists Jorgen Goul Andersen and Mette Tobiasen (2004) found in a study of Danish consumers that individuals who buycott consumer goods do not generally distrust political institutions.[355] Economists Carola Grebitus, Monika Hartmann, and Nina Langen (2009) found in their experimental auctions and choice experiments with 38 German students that whether the participants had donated to charity in the last year or not had no significant association with willingness to pay for different coffee types (conventional, organic, Fair Trade, organic and Fair Trade, or “cause-related marketing coffee”).[356] Sociologist Kathryn Wheeler notes from UK survey data that individuals who selected “Buying fair-trade goods” as first or second when asked: “In which ways, if any, do you think you as an individual can most effectively contribute to reducing poverty in developing countries?” were more likely to also believe that “Government should be working for a fairer trading system” after controlling for other factors.[357] Some of Wheeler’s interviewees from Chelmsford, UK also seemed to both proactively buy Fair Trade products and support other forms of charitable and political activity.[358]

These findings do not necessarily mean that participation in political consumerism increases an individual’s likelihood of engaging in other forms of activism; the associations in the surveys above could be explained by lurking variables, such as dedication to Fair Trade, moral motivations, conscientiousness, political engagement, and so on. The results suggest that if social movements encourage their supporters to undertake consumer action, this will not substantially reduce their willingness to engage in other forms of activism.

There is a broad literature on political consumerism that has not been fully explored here. Sociologists Jörg Rössel and Patrick Henri Schenk (2018) summarize that, “[p]olitical consumption is a flourishing field of research… Some authors suspect that [political consumption] may distract citizens from more challenging forms of participation (crowding-out thesis). In contrast, most empirical research has shown that political consumers are also more active than the general population in other forms of political participation.”[359] The results from their own study show that, “fair trade consumption is only weakly related to other forms of engagement for Global South issues, thus it does not distract from more challenging forms of engagement, but it is also not part of a more general engaged lifestyle.”[360]

- Providing consumer action opportunities might be a valuable addition to a social movement’s repertoire, even if they are not the most cost-effective actions that an impact-focused individual could take.

Individuals may choose to purchase Fair Trade or other ethical products that have a price premium compared to conventional products. Alternatively, a highly impact-focused consumer could spend the same amount of money but divide it between the purchase of a cheaper, less ethically produced item and a charitable donation that directly benefits stakeholders that the consumer wishes to help. For example, instead of purchasing a Fair Trade banana, a consumer could purchase a conventional banana and then donate to GiveDirectly, a nonprofit that makes unconditional cash transfers to some of the world’s poorest people.[361] After considering each of these options, you might reasonably conclude that the latter option is more cost-effective for achieving your altruistic goals.[362] However, not everyone donates,[363] let alone makes these sort of cost-benefit calculations. Individuals who do not donate might still be encouraged to engage in political consumerism, and donors might be encouraged to engage in political consumerism in addition to the donations that they already make.[364] Therefore, even if purchasing more ethical but more expensive products is not cost-effective for highly impact-focused individuals because it reduces the donations that they can make, it may still be cost-effective for a social movement to promote consumer action opportunities.[365] For example, Nicholls and Opal estimate that every dollar spent by a member national initiative yields $2.80 in increased farmer income.[366]

Institutional Reform

- Victories can likely be won through campaigns pressuring institutions, even with relatively low investment of movement resources.

The organization Global Exchange has had some success through its pressure campaigns against companies and public institutions,[367] despite having lower funding than organizations focusing on consumers.[368] However, a survey of 14 businesses in Seattle in 2003 suggests that, “[t]hreats of negative publicity and/or picketing by Fair Trade activists” was a far less important factor in their decisions of whether or not to sell Fair Trade coffee than considerations of quality, demand, or price.[369]

- It may be important to lobby for favorable international regulations.

Unfavorable tariffs and international trade regulations seem to have made it difficult for Fair Trade to be both profitable for Northern businesses and beneficial for producers in the Global South.[370] The collapse of the International Coffee Agreement seems to have caused problems for producers and may have encouraged the development of Fair Trade coffee.[371] Some scholars argue that improved international regulations need to be part of the effort to support impoverished producers in the Global South.[372] Nevertheless, the Fair Trade movement has only made limited efforts to lobby national politicians or international institutions for favorable trade regulations.[373] Of course, lobbying to change international trade regulations could have been expensive and ineffective, so it is unclear whether more investment in lobbying would really have been a cost-effective use of movement resources.

- There may be opportunities for low-cost, grassroots initiatives in local politics that promote support for consumer movements.

Fair Trade towns do not seem to have been well-funded or supported by central movement organizations.[374] Nevertheless, there are apparently now 2,030 Fair Trade Towns in 34 countries.[375] These initiatives do not ban particular product types but offer support and targets to encourage higher availability of the desired product types.[376]

- Social movements engaging with market mechanisms may be able to draw substantial funding from for-profit organizations.