Edited by Jacy Reese Anthis and Kelly McNamara. Many thanks to the researchers who provided feedback or checked the citations of their work, including Rosemary Nossiff, David Garrow, Daniel K. Williams, Linda Greenhouse, Raymond Tatalovich, Alesha Doan, Matthew Wetstein, and R. Alta Charo. Thanks to Joey Savoie for discussion on case study methodology.

Abstract

This report aims to assess (1) the extent to which the modern (1966-2019) anti-abortion movement in the United States can be said to have successfully achieved its goals, (2) what factors caused the various successes and failures of this movement, and (3) what these findings suggest about how modern social movements should strategize. The analysis highlights the farmed animal movement as an illustrative example of the strategic implications for a variety of movements. Key findings of this report include that encouraging legal change without popular support can provide momentum for a social movement’s opponents; legislation and direct action may be effective at reducing supply through disruption and burdensome regulation, but direct effects on demand are smaller; and close alignment with political or religious groups may be tractable but risks longer-term stagnation.

Table of Contents

Introduction

The US anti-abortion movement, also known as the pro-life or right-to-life movement, argues that human life begins at conception and that the human fetus has a right to life. Its advocates support, at least in part, an expansion of the moral circle to encompass unborn human fetuses. Although there are important differences between the US anti-abortion and farmed animal protection movements, there is a fundamental similarity between them: Advocates from both movements believe the entities they seek to protect are granted insufficient consideration, protection, or rights and that it is worth investing time and resources into securing more consideration, protection, or rights for them. Other features that affect the anti-abortion movement’s comparability with the farmed animal movement are listed below, but overall it seems we can glean some strategic insight from the anti-abortion movement suitable for effective animal advocacy—that is, information that can be used to understand how to maximize the impact of interventions used.[1]

Importantly, this report makes no attempt to evaluate the goals of either movement. This report is exclusively about the strategy of social movements, and while we will discuss goals insofar as they are relevant to strategic discussion, we deliberately avoid any moral assessment.

US farmed animal advocates tend to favor less restrictive abortion regulations, so we know that some might be hesitant to take seriously a report that looks for insight in the strategy of the anti-abortion movement. We think this is actually a strong reason to study this movement, because it is so different and therefore might have unusually interesting lessons to be gleaned. We hope readers will keep an open mind and attempt to examine the strategy of this movement, and other social movements, with an objective lens.

This report provides a condensed history of the US anti-abortion movement, from the 1960s to the present. After providing this history, the report draws tentative conclusions about which strategies seemed to be most effective for the anti-abortion movement and suggests potential implications for the farmed animal movement’s strategy. The focus of this report is on strategic insights for the farmed animal movement, but some insights may be useful for other movements as well.

This report focuses on the US anti-abortion movement, rather than international efforts, for three reasons:

- It seems that abortion issues have been highly salient in US politics and society since the late 1960s, and especially since around 1980, compared to other countries. This suggests that both the anti-abortion movement and abortion rights movements would both have been larger in the US than in other countries that could have been studied and that there would be more content worth evaluating.

- Much activity and research of the effective animal advocacy community has focused on the US.[2] This concentration of resources is at least partially justified by the strategic importance of the US as a country with a large number of animals in factory farmed conditions and substantial social, political, and economic influence over the rest of the world. Given the research gaps in our understanding of effective animal advocacy in the US,[3] it also seems reasonable to focus on coming to stronger conclusions for the optimal movement strategy in that context, before seeking to test whether those conclusions hold in other contexts.

- After initial research on the topic, it became clear that there was a plethora of surveys, social scientific research, and historical research on the topic of abortion in the US. Limiting the breadth of content to the US only reduced the resources required to complete this report, hopefully without a correspondingly large loss to the completeness and usefulness of the report.

This report was mainly undertaken as exploratory analysis, rather than being designed to test explicit hypotheses on strategic effectiveness, though the author initially suspected that the report would provide strategic insight into the question of whether a left-wing or nonpartisan focus is more desirable for the farmed animal movement, as well as other foundational questions in effective animal advocacy.[4] The author also believed that the anti-abortion movement had mostly failed at achieving its goals, and therefore the report would provide evidence that, on average, the tactics used by the anti-abortion movement should be avoided by the farmed animal movement. This is unlike most EAA case studies,[5] in which researchers have analyzed successful movements and therefore tend to take their use of a tactic as evidence of its effectiveness.

As with Sentience Institute’s report on the British antislavery movement, the farmed animal movement as this report describes it is weighted towards the US movement, so readers from other regions may see different similarities and differences between the US anti-abortion movement and their own region and movement, and should adjust the applicability of this report’s conclusions to their own region’s advocacy accordingly. This report assumes the reader has some knowledge of modern animal farming and animal advocacy.[6]

The anti-abortion movement is called a variety of names, including “pro-life,” “right to life,” and “anti-choice.” In comparison, the abortion rights movement is called “pro-choice,” “pro-abortion,” or “pro-death.”[7] In this report, the terms “anti-abortion” and “abortion rights” are used respectively for consistency. These terms are used to refer to the US movements specifically, rather than international movements. Given the US context, the term “liberal” when referring to abortion laws or attitudes implies greater support for abortion rights. What this report refers to as “crisis pregnancy centers” have been called a variety of names, including “Birthright and Emergency Pregnancy Services (EPS),” “Problem Pregnancy Centers (PPCs),” “Pregnancy Resource Centers (PRCs),” “A Woman's Concern Health Centers,” and “Life Choices Medical Clinics.”[8] Although the term is avoided here due to its imprecision, other authors sometimes use the term “therapeutic abortions,” which refers to abortions performed to protect the health (sometimes including mental health) or life of the mother. Abortions performed for other reasons are sometimes referred to as “elective abortions.”[9] The term “fetus” is used throughout this report.[10]

Finally, this report borrows much of the methodology and framing of Sentience Institute’s 2017 report on the British antislavery movement.[11]

Summary of Key Implications

A single historical case study does not provide strong evidence for any particular claim; the value of these case studies comes from providing insight into a large number of important questions.[12] This section lists a number of strategic claims supported by the evidence in this report:

- Political parties are more willing than expected to modify their stance on controversial issues, even in a direction that seems contrary to the views of their existing supporter base.

- Even if the theology of a particular religion has unclear implications for the moral issues of interest to social movements, a strong moral stance can still become normalized within a religious community that is highly influential in society at large.

- Disruptive and confrontational tactics seem likely to be effective at reducing the supply of targeted products or services, but direct effects on demand are smaller. They may also increase issue salience among policymakers and the public. Activists using such tactics should strive to minimize possible negative effects, such as legal restrictions and damage to the credibility and reputation of the movement. Violent tactics seem generally unproductive but some disruptive tactics could be worth the associated risks as measured by activist goals.

- Legislation that restricts access to abortions seems to have successfully reduced the number of abortions. Though the effect may be small, it is possible that it would be higher on products or services for which the demand is more elastic, such as animal products. This legislation does not seem to have substantially reduced the public's support for further incremental legislation.

- For securing desired legislative outcomes at both the state and national levels, securing the support of politicians seems more important than favorable public opinion. A favorable legal environment (e.g. supportive judges) also seems important.

- Expending substantial resources on encouraging legal change without popular support for the proposed measures seems inadvisable. Highly salient legal changes may provide momentum to opposition groups. Legal rulings seem to have little, if any, positive effect on public opinion regarding controversial issues, though they may consolidate support for issues that were already widely accepted. There is also some evidence that such changes may polarize opinion on controversial issues, although other analyses dispute this.

- Close association with controversial interest groups may reduce the credibility and durability of a movement, and may lead to increased factionalism and polarization on relevant issues.

- Stronger alignment with a major political party might temporarily speed up progress by increasing the rate at which legislation is proposed but may also increase the chances of longer-term stagnation by encouraging political deadlock on an issue that could otherwise have transcended party politics.

- High issue salience may contribute to political polarization and, more tentatively, to stagnation. Advocates should only focus on increasing issue salience if the timing is beneficial.

- Boycotts of specific companies across their entire product range may be a more promising tactic for disrupting the supply of a product than boycotts of a specific product type across all companies. Additionally, companies trying to bring a new product to market can protect against boycotts by remaining narrowly focused, and avoiding merging with or being acquired by larger companies with more diverse product types.

- There is indirect evidence that proactive, often confrontational, face-to-face “counseling” outreach causes a backfire effect, making individuals less supportive of a movement’s goals.

A Condensed Chronological History of the Anti-Abortion Movement

This condensed history of the US anti-abortion movement is not intended to imply causal relationships between listed events, unless stated explicitly. For example, if a sentence referring to a change in the legal context is followed by a sentence about changes in abortion rates, the two should not be assumed to be connected. Causation is discussed more explicitly in the section on “Strategic Implications.” This section of the report is not intended to present a comprehensive narrative; it condenses the history into events and processes that have strategic implications for modern social movements.[13] There are slight deviations from chronological order used for clarity.

Early History of the Movement

When the US was declared independent from Great Britain, English common law forbade abortion after “quickening,” the start of fetal movements.[14] Some states began to make abortion at any stage of pregnancy[15] illegal in the 19th century, and by the 1960s abortion was a felony in most states, except for when the mother’s life was in danger.[16] This early anti-abortion movement operated in very different circumstances to the movement from the 1960s onwards, and the causes of its success are probably different to the factors affecting the successes and failure of the more modern movement.[17]

In 1923, the Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau and the American Birth Control League were established. These organizations, initially focused on birth control, later merged to become Planned Parenthood Federation of America.[18]

Although there was little discussion of or campaigning on abortion in the US in the early and mid 20th century,[19] laws that increased abortion rights were passed in several countries in Eastern Europe and Scandinavia.[20]

Joseph Fletcher’s Medicine and Morals and Harold Rosen’s edited volume, Therapeutic Abortion: Medical, Psychiatric, Legal, Anthropological, and Religious Considerations, published in 1954, considered circumstances in which abortion might be permissible or preferable.[21]

From January 1955 until January 1981, the Democrats held a majority in both the Senate and the House of Representatives.[22]

In 1955, Mary Calderone, the director of Planned Parenthood, convened a secret conference on abortion,[23] the attendees of which were predominantly medical and psychiatric professionals, though public health officials and researchers also attended.[24] In 1958, Planned Parenthood published Abortion in the United States, a written record of the conference.[25] The introduction to the book frames abortion as both a medical and social problem, expressing concern for the suffering of women,[26] though not all contributions were quite as sympathetic.[27] According to political scientists Raymond Tatalovich and Byron W. Daynes, this book, like the write-up of a 1942 conference on abortion, “was given little critical review.”[28] However, historian David Garrow argues that, “[d]espite its own timidity, the Calderone volume nonetheless occasioned book reviews that gave voice to nascent liberalization sentiments.”[29] These books and four other books published before 1960 on the topic of abortion were written by a mixture of medical, psychiatric, and legal professionals.[30] Alan Guttmacher, an obstetrician/gynecologist, later to become president of Planned Parenthood, was publicly advocating for abortion reform at this time, though his views were controversial even among medical professionals and he was known to be an outspoken liberal.[31]

In October 1958, a member of the standing committee of the American Civil Liberties Union’s board of directors argued to her ACLU colleagues that “there was an important individual right that should be given weight. A woman should have the right to determine whether or not she should bear a child.” This was the second time she had raised the issue in two years.[32] There is other evidence that concern for women’s autonomy in situations including, but not being limited to, conception resulting from rape motivated support for reform in these early years of abortion rights advocacy.[33]

In 1959, the American Medical Association endorsed the availability of birth control[34] and the American Law Institute (ALI) advocated for abortion to be made legal in situations of rape, incest, fetal deformity, or if the pregnancy risked the mother’s physical or mental health.[35] Garrow claims that “[a] number of law reviews also published articles endorsing the ALI therapeutic reform proposal, but the Georgetown Law Journal published a two-part, 220-page attack on the burgeoning liberalization drive.”[36] A variety of arguments have been advanced for the growth in support for abortion rights at this time.[37] However, advocacy for reforms to abortion law seems to have continued to be primarily the preserve of medical and legal professionals.[38] For example, a study of hospital practices in California was published in 1959, with the authors arguing that abortion should be decided by medical professionals and not by criminal law.[39]

In 1960, a bill was introduced in California following the ALI’s guidelines, but it was tabled when representatives of the Catholic Church announced their intention to oppose the bill.[40] In 1961, the New Hampshire Medical Society prepared and sponsored legislation to make abortion to save a mother’s life legal before the fifth month of pregnancy, extending the existing legislation which made such abortions possible at subsequent points in the pregnancy.[41] This prompted resistance from Catholics and conservatives, and although the state’s legislature approved the bill, it was vetoed by the governor.[42] Other proposals for legal relaxations of the restrictions on abortion began to be made at around this time.[43] For example, in November 1958, an article in America magazine condemned recent support for moves towards abortion liberalization as advocating “a regression to barbarism.”[44] Of course, resistance can take many forms; there was likely a degree of resistance wherever liberalized laws were considered, such as opposition from some legislators and public condemnation by the Catholic clergy.[45]

The 1962 case of Sherri Finkbine, who travelled to Sweden to get an abortion after taking thalidomide and the 1964 outbreak of rubella brought the question of the legitimacy of abortions for medical reasons to greater prominence.[46] From 1962 on, the number of articles on abortion in popular magazines, newspapers, and social science journals increased. For example, one index of periodical publications includes 19 references to the abortion issue in 1962, compared to 6 in each of the previous 3 years. The number of published periodical references to abortion in the years 1966 to 1981 was more than six times the number in the years 1950 to 1965.[47]

At some point between 1962 and 1965, one of the first abortion rights organizations, the Society for Humane Abortion (SHA), was formed. They distributed copies of talks by the biologist Garrett Hardin; Hardin and SHA activists argued for abortion liberalization on feminist grounds, urging that women be granted bodily autonomy.[48] In 1964, the Committee for a Humane Abortion Law (soon renamed the Association for the Study of Abortion) was founded in New York by a mixture of physicians and those outside the medical profession; it elected a physician as leader, with one committee member explaining to Alan Guttmacher that “the future of the organization can best be served by a physician in the role of chairman.”[49]

In 1963, a British lawyer published a book called The Right to Life, which discussed the point at which life begins and the sanctity of human life. The book discussed abortion alongside euthanasia, the death penalty, and war.[50]

Between 1962 and 1966, five states rejected legislation similar to the moderate reforms suggested by the American Law Institute.[51] Further reforms continued thereafter,[52] though anti-abortion resistance was successful in some states.[53]

In 1965, the Supreme Court decision in Griswold v. Connecticut invalidated the last remaining anticontraceptive state laws in Connecticut and Massachusetts.[54] Importantly for subsequent legal decisions regarding abortion, as Rosemary Nossiff summarizes, “the Court held that a Connecticut law that prohibited the sale of contraceptives to married couples was unconstitutional because it violated the individual’s right to be left alone, as guaranteed by the First, Fourth, Fifth, and Ninth Amendments.”[55] The later case of Eisenstadt v. Baird (1972) extended this ruling to unmarried relationships,[56] meaning that the use of contraceptives was now legal in all 50 states for adults.[57]

In the 1960s and 1970s in various parts of the world, legislation permitting abortion was passed, either in specific circumstances or whenever it was sought.[58] Laws in most US states permitted abortion only if the life of the mother was endangered. In 1966, Mississippi reformed its laws to also permit abortion for survivors of rape. Unlike subsequent more liberal reforms, this law did not include reference to the mother’s physical or mental health.[59]

1966-73: Legalization of abortion in some states and initial anti-abortion resistance

From around 1966, media coverage of abortion issues increased.[60]

In 1966, Edward Golden of New York formed a small group to resist proposed changes to liberalize the state’s abortion laws.[61] This seems to have been some of the first anti-abortion mobilization beyond resistance to reform from Catholic clergy and state legislators.[62] In December of the same year, a Cardinal in California organized the first meeting of the Right to Life League.[63] The Virginia Society for Human Life was founded in 1967 as the first formal state-level anti-abortion organization in the US.[64] Over the course of the next few years, anti-abortion activists and groups in other locations also began fighting further legislative changes at the state level.[65]

By the mid 1960s, the media and Catholic writers were contributing to the debate on abortion.[66] In 1966, the Catholic Church’s organizational presence in the US was reformed, creating the National Conference of Catholic Bishops (NCCB) and the United States Catholic Conference (USCC).[67] The NCCB asked Reverend James T. McHugh, director of the Family Life Bureau of the USCC, to begin documenting legislative efforts to liberalize abortion policy.[68] The Catholic Church had long held strict policies against abortion, at least as early as 1398, and had a more clearly anti-abortion tradition than other Christian denominations.[69]

In 1966, the Termination of Pregnancy Bill to liberalize abortion law was proposed in the United Kingdom. This sparked the launch of the Society for the Protection of Unborn Children (SPUC) in the UK in January 1967.[70] The group was unable to stop the Abortion Act, which permitted abortion to avoid health risks, from being passed in 1967.[71]

In September 1967, the first International Conference on Abortion was held in Washington D.C.[72] The USCC sent information about proposed abortion legislation to state Catholic Conferences, held meetings to build resistance, and communicated with the bishops, urging the importance of the issue.[73]

In 1967, Colorado legalized abortion in cases of rape, incest, or when pregnancy would lead to permanent physical disability of the woman. Between 1967 and 1972, twelve other states reformed their laws to permit abortions under some or all of these circumstances.[74] In 1967, surveys of 40,089 physicians conducted by Modern Medicine and of the American Psychiatric Association’s membership found support for abortion when there was a risk of the mother’s death (77% and 97% respectively) but not whenever requested, for any reason (14% and 24%).[75]

Sociologist Suzanne Staggenborg notes that in the late-1960s, the grassroots of the abortion rights movement were made up of “[w]omen, college students and other young people who were activated by earlier movements of the 1960s.” Supporters of abortion rights seem to have had diverse motivations; Staggenborg notes that organizational support was provided by “[t]he family-planning population, and women’s movements” and that “the Women’s National Abortion Action Coalition (WONAAC) was formed in 1971 by members of the Socialist Workers Party.”[76] Focusing on evidence from California, Kristin Luker similarly argues that during the 1960s, the movement for abortion reform shifted from comprising predominantly medical and legal professionals to including the wider women’s movement.[77] The population control movement seems to have become more involved in the push for abortion reform in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[78]

In 1968 Pope Paul VI issued the encyclical Humanae Vitae that reaffirmed the Catholic doctrine that contraception is immoral.[79] The link made between the issues of contraception and abortion was controversial within the leaders of the anti-abortion movement.[80]

That same year, the National Right to Life Committee (NRLC) was formalized and stated goals in its first newsletter of improving communication in the anti-abortion movement and of setting up new local groups.[81] The NRLC encouraged the creation of new state-level anti-abortion groups, then coordinated and supported them.[82] Its influence was limited; historian Prudence Flowers notes that before 1973, “It had almost no funds, was run out of the offices of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops, did not direct the activities of affiliated chapters, and took three years to hold its first formal meeting for state right-to-life leaders.”[83] It has been estimated that 250 state and local groups were affiliated with NRLC by mid-1972.[84] Some funding for state groups came from the Catholic Church.[85]

Another notable event of 1968 was the founding of Birthright International in Canada, providing alternative services to abortion clinics through crisis pregnancy centers (CPCs).[86] CPCs seek to provide support to pregnant women and new mothers.[87] Staff often also attempt to dissuade women who attend the CPCs from having abortions.[88] Apart from a single example from Hawaii in 1967, Birthright International seems to have organized the first CPCs.[89] From about 1969, several anti-abortion books were written, which variously included discussion of legal, theological, moral, and anti-industry themes.[90]

Around this time, there were many legal challenges to laws restricting abortion in the courts.[91] The September 1969 California Supreme Court ruling of People v. Leon P. Belous stated that California’s pre-1967 antiabortion law was unconstitutionally vague in only pemitting abortion if it was “necessary to preserve” a pregnant woman’s life. The four-to-three majority ruling also asserted that, “[t]he fundamental right of the woman to choose whether to bear children follows from the Supreme Court’s and this court’s repeated acknowledgement of a ‘right to privacy’ or ‘liberty’ in matters related to marriage, family, and sex.”[92]

Also around this time, there was some internal debate in the abortion rights movement as to whether it should advocate for an increased number of exceptions to abortion restrictions or for a repeal of all abortion restrictions. The former case had been advocated by the American Law Institute, the Association for the Study of Abortion, and Alan Guttmacher, but the National Organization for Women had made a resolution in favor of repeal in November 1967.[93] In 1969, the National Association for Repeal of Abortion Laws (NARAL, later renamed the National Abortion Rights Action League) was formed; that year, it held the First National Conference on Abortion Laws in Chicago and openly sided with a medical group performing abortions after referrals from NARAL members.[94] The group was at least partly driven by feminist ideals.[95]

Staggenborg argues that in the years around 1970, the abortion rights movement pursued non-confrontational strategies, including education and lobbying, but lacked the resources to do so with much success. Women’s liberation groups also used direct action and confrontational tactics to press for abortion rights at this time, including disrupting the American Medical Association’s conference to protest its lack of support for abortion rights and using public demonstrations, such as the “Children by Choice” national action day.[96] One article presents the abortion rights movement at this time as an “uneasy” alliance of physicians and feminists.[97]

Between 1967 and 1970, campaigners for abortion liberalization in Hawaii gathered endorsements from a range of religious, medical, and other influential groups, as well as support from both Democrat and Republican state politicians. In contrast, anti-abortion campaigners in the state relied heavily on Catholic organizational support. Though both sides used petitions, mail, telephone, and face-to-face campaigning techniques, it seems that only the anti-abortion advocates used mass demonstrations.[98]

In 1970, Hawaii legalized abortions at the request of the woman for any reason, at any point in the pregnancy,[99] and New York, Alaska, and Washington followed (in Washington’s case, following a referendum in 1970).[100] Political scientists Raymond Tatalovich and Byron W. Daynes characterize the arguments voiced for reform in Washington as having been “the problem of unwanted children, the implications of having illegal abortions, and the discriminatory nature of seeking abortions elsewhere.” In contrast, anti-abortion advocates raised moral concerns such as “the sanctity of human life.”[101] After successful resistance efforts in previous years, the Catholic Church in New York seems to have become complacent that abortion liberalization could be resisted with minimal mobilization.[102] Anti-abortion legislators may have made a similar mistake.[103] The New York legislature only passed the liberalization bill by a single vote.[104] One leading anti-abortion activist in the state attributed this defeat to insufficient lobbying efforts.[105] These new abortion rights laws seem to have encouraged some anti-abortion backlash; subsequently, abortion reform bills were rejected in several states, perhaps due partly to lobbying efforts,[106] and the membership of New York’s anti-abortion movement grew.[107] After anti-abortion demonstrations and lobbying, in 1972, New York’s legislature voted to repeal the liberal abortion law that had been introduced in 1970, but this repeal bill was vetoed by the Governor.[108]

That same year, the Republican senator Bob Packwood proposed the “National Abortion Act” to secure the “fundamental and constitutional rights” of women. Political scientist David Karol notes that this was the first proposed federal legislation on abortion.[109] Important also, the American Medical Association took a more favorable public stance on abortion rights.[110]

In April 1971, in United States v. Vuitch, the Supreme Court permitted a D.C. law banning abortion except when necessary to protect the health or life of the woman. However, the court’s emphasis on the importance of doctors’ professional judgement in approving abortion procedures reflected a focus on medical (as opposed to moral) considerations that would become significant in the 1973 Supreme Court decisions.[111]

In August 1971, Americans United for Life (AUL) was formed as a national organization. Its focus was initially on education.[112] In 1971, Alternatives to Abortion International (later renamed Heartbeat International) was founded by 60 crisis pregnancy centers.[113] In 1971, John Willke of Cincinnati Right to Life produced a four-page color pamphlet called Life or Death, which, according to anti-abortion activist and historian Robert Karrer, “became the most widely used anti-abortion tract during the 1970s and was translated into many languages.”[114]

A poll in September 1972 suggested that 59% of Michigan voters favored supporting an upcoming referendum to permit abortion through the first twenty weeks of pregnancy without requiring state residency. In November, however, 61% voted against the referendum.[115] This apparent change in public opinion was potentially caused partially by anti-abortion activism. Karrer summarizes that, beginning in September, the group Voice of the Unborn waged a “short but effective campaign”:

‘The humanity of the child is the only issue,’ stated Richard Jaynes, a Detroit-area physician and president of the coalition. ‘Nobody has the right to deprive him of his life—not even his mother.’ Working with the Michigan Catholic Conference (that sponsored the campaign “Love and Let Live” with the 950 Catholic parishes in the state), anti-abortion volunteers distributed literature to tens of thousands of homes, primarily the Willke brochure ‘Life or Death.’ Willke came to the state late in the campaign, visiting several mid sized cities to speak against the referendum and promote his ‘Life or Death’ tract. The tide turned in the final two weeks. That November, Voice of the Unborn garnered 61 percent of the vote and swiftly established itself as one of the most effective anti-abortion groups in the country.”[116]

In the same month, voters in North Dakota rejected a referendum to liberalize abortion laws, by 77% to 23%.[117] Similar tactics seem to have been involved, including voter mobilization through speaking engagements and distribution of the pamphlet Life or Death.[118]

During the presidential election campaign of 1972, Republican president Richard Nixon asserted an anti-abortion stance (no prior US president seems to have discussed the issue so publicly and assertively), while George McGovern, the Democratic candidate, tried to avoid the issue. Nixon was re-elected.[119]

On December 9, 1972, the board of the National Right to Life Committee (NRLC, the largest national anti-abortion organization, with 250 affiliated state and local groups[120]) voted to sever official ties with the Catholic Church and to restructure the organization. This seems to have been caused by several factors, including a desire for the NRLC to accurately represent the views of local organizations, a desire for the NRLC to be well-placed to retain a national leadership position within the anti-abortion movement, and concerns that ties to the USCC were preventing fundraising for lobbying.[121]

Though their influence within the Party remained limited, feminists sought to add an abortion rights plank to the Democrats’ election platform at the 1972 Democratic Convention. Earlier that year, Democratic Representative Bella Abzug had proposed a national bill for abortion rights.[122]

Between 1966 and 1973, 13 states had passed laws permitting abortions to protect the woman’s physical and mental health, 1 to allow abortions after rape, and 4 had legalized abortion for any reason. With the exception of 3 states that prohibited abortion in all circumstances (Louisiana, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania), all other states prohibited abortion except when the woman’s life was in danger.[123] Some states had rejected liberalized legislation by large margins.[124] There is evidence that women would travel from states where abortion was illegal to states where they could have the procedure.[125] Internationally, Tatalovich and Daynes count that, “Only 15 nations predated the United States in [liberalizing] abortion reform,” mostly in Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, and that “only 6 other countries allowed abortion ‘on demand’ in 1974.”[126]

1973-80: Roe v. Wade, anti-abortion mobilization, and political tactics

The January 22, 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling enforced a national framework for state legislation that decriminalized abortion for up to twelve weeks of pregnancy (the end of the first trimester). After this point, a woman could obtain an abortion for health reasons.[127] This landmark decision was likely encouraged by the abortion rights activism of the past two decades.[128] Legal scholars Linda Greenhouse and Reva Siegel argue that “doctors and public health advocates played an important role in setting the nation on the road to Roe, but so too did movements for human freedom… As the women’s movement connected the abortion right to these larger claims of principle, the abortion conflict was constitutionalized.” Nevertheless, they note that the Supreme Court justified its decisions largely with reference to medical arguments, rather than moral ones.[129] The legal precedent of recent court decisions such as Griswold v. Connecticut, which had ruled that the Constitution protects the right of marital privacy against state restrictions on contraception,[130] was cited in the Roe ruling as justices weighed the right to privacy of those seeking abortion against the interests of the state.[131]

On the same day as the Roe ruling, the Doe v. Bolton ruling clarified that a variety of factors, “physical, emotional, psychological, familial, and the woman’s age,” could influence a medical decision to permit a late termination of pregnancy.[132]

The Republican party did not yet have a consensus position on abortion and so issued only a brief statement in response to Roe v. Wade, repeating Nixon’s view that abortion should not be used for “population control,” without commenting directly on the ruling.[133] Likewise, Evangelical leaders adopted various positions on the issue, or passed little comment on the decision, though there was some agreement on “a high view of the sanctity of human life, including fetal life.”[134]

Many anti-abortion activists were surprised by the court ruling.[135] There is anecdotal evidence that these two legal rulings catalyzed some activists’ deeper involvement in the anti-abortion movement. For example, sociologist Ziad Munson notes that a “handful” of his activist interviewees “became mobilized immediately after the Supreme Court rulings.”[136] Several right-to-life organizations saw a surge in engagement and support; Minnesota Citizens Concerned for Life’s membership rose by 50% in 4 months,[137] and Michigan Citizens for Life’s membership rose from 10,000 in late 1972 to 50,000 in May 1973 and to 200,000 in 1976.[138] At least one new national anti-abortion group was formed.[139] Additionally, the June 1973 NRLC national convention had about 1,500 attendees from 46 states and Canada, a large increase from the previous conference in June 1972, which had had 280 to 380 attendees. Changes in organization at the NRLC may partially account for this difference, however.[140]

On January 30, 1973 (8 days after Roe v. Wade), Congressmen Lawrence Hogan proposed the first Human Life Amendment (HLA)[141]—that is, an amendment to the constitution to overturn the ruling of Roe v. Wade and to outlaw abortion.[142] Hogan’s proposed HLA stated that neither federal nor state government “shall deprive any human being, from the moment of conception, of life without due process of law.” Two other HLAs were proposed that year. Although one of these reached a Senate subcommittee vote in September 1974, it was rejected by a 5 to 2 vote.[143] Many HLAs have been proposed subsequently.[144] In the wake of Roe, Rhode Island, West Virginia, Indiana, and Utah sought to introduce new anti-abortion state legislation, but the new laws were struck down by courts in several of these states.[145] Other restrictive state-level anti-abortion legislation was maintained, however, at least in part.[146]

In addition to supporting HLAs, anti-abortion legislators pursued legislation at the state level. Political scientists Scott H. Ainsworth and Thad E. Hall note that 1973-84 saw a mean of 37 proposals per year.[147]

Between 1972 and 1973, national polls showed a rise in support for abortion rights in the population as a whole. Support had been rising in previous years and continued to rise subsequently.[148]

On December 8, 1973, the NRLC board agreed that the “first program priority” was “the development and implementation of a political campaign to effect passage of a Human Life constitutional Amendment.”[149]

Shortly after the Roe v. Wade ruling, the board of Americans United for Life (AUL) gave control to a medical attorney, Dennis J. Horan, who shifted AUL’s focus away from education and towards a legal strategy, though they continued to publish books setting forth moral arguments. By 1976, the group had formed the AUL Legal Defense Fund.[150] AUL won four of the seven Supreme Court cases between 1975 and 1981 in which they sponsored litigation or submitted amicus curiae briefs (a method of offering information and expertise relevant to a case), though this is a small number of cases compared to other interest groups.[151]

In the years after Roe, there seems to have been a shift away from population control arguments in the abortion rights movement;[152] population control organizations stepped away from the abortion rights movement[153] and other organizations seem to have distanced themselves from population control rhetoric.[154] Some anti-abortion activists also focused on refuting the rights arguments discussed in the Roe ruling.[155] Both the abortion rights and anti-abortion movements seem to have made some effort to explore possible compromises between women’s rights and fetus’ rights.[156]

On January 22, 1974, the anniversary of the Roe v. Wade decision, the first March for Life was held. These protest rallies have continued to be held annually in Washington, D.C., organized by the March for Life Education and Defense Fund.[157]

Anthropologist Carol J. C. Maxwell notes that, “[i]n the mid 1970s, abortion clinics in the United States experienced their first sit-ins.”[158] A group called Catholics United for Life engaged in clinic protests and sidewalk counselling — where anti-abortion activists stood outside abortion clinics and attempted to dissuade pregnant women from entering the clinic or choosing to have an abortion — from the mid- to late-1970s.[159] However, other accounts of anti-abortion direct action do not mention direct action protests this early.[160] This omission suggests that these protests remained small-scale and localized for several years.

During the years after Roe v. Wade, abortion rights groups professionalized and built up organizational stability. For example, NARAL hired new staff, used direct-mail techniques to raise money, and set up a political action committee.[161]

In 1975, the National Council of Catholic Bishops (NCCB) launched a campaign for an amendment of the US Constitution to reverse the Roe v. Wade decision.[162]

In September 1976, the Hyde Amendment, an amendment to a fiscal measure proposed to the House of Representatives by Republican Henry J. Hyde, prevented the use of certain federal funds for abortions, principally through Medicaid. Initially rejected by the Senate, the measure was passed once an exception was included to allow funding for abortions that would prevent “severe and long-lasting physical health damage.” Prior to this, approximately 300,000 abortions per year were funded by Medicaid.[163] After the Hyde Amendment, some states continued to use their own funds to cover abortion for those on Medicaid.[164] Despite the continued failure of HLA tactics, funding restrictions were passed again subsequently, as with 1978 modifications to three bills.[165]

In 1976, the Supreme Court’s decision in Planned Parenthood v. Danforth declared unconstitutional a Missouri law that gave husbands or parents of unwed minors the ability to veto their decision to have an abortion.[166] However, informed consent laws (requiring the woman to be aware of certain factors, such as the extent of fetal development) were upheld and the ruling suggested that other restrictions on abortion could be allowed in the first trimester of pregnancy.[167]

In the buildup to the 1976 election, Democratic candidate Jimmy Carter and Republican candidate Gerald Ford sought to reassure the NCCB about their position on abortion. Archbishop Joseph Bernadin, the president of the NCCB, noted that he and the NCCB were “disappointed” with Carter’s position on abortion, while Ford’s position was “encouraging.”[168] Carter won the election and became president in January 1977. The two major political parties were not yet clearly split in Congress on the issue of abortion, however,[169] and both presidents had mixed views, supporting the implementation of the Hyde Amendment, but not supporting a HLA.[170]

In the 1970s, evangelicals had been increasingly mobilizing on conservative political campaigns and issues.[171] Jimmy Carter was an evangelical Protestant. His election as president may have encouraged evangelical politicization, given his open claims that “I’ll be a better president because of my deep religious convictions,” and admission that his “deep and consistent religious faith” was “the most important thing in [his] life.”[172] Despite encouraging a perception that his politics were inspired by faith, his moderate liberal politics differed from those of many evangelicals,[173] and frustration with his policies seems likely to have encouraged a shift towards the Republican Party among conservative Christians.[174]

The Hyde Amendment survived four Supreme Court rulings on cases brought by abortion rights groups: Beal v. Doe, Maker v. Roe, and Poelker v. Doe, each in 1977, and Harris v. McRae in 1980.[175]

In 1977, the first organization dedicated to securing the election of anti-abortion candidates, the Life Amendment Political Action Committee, was created. The NRLC later created its own organization, NRLCPAC, which, according to historian Keith Cassidy, “became the largest pro-life PAC.”[176]

From late 1976 until 1979, anti-abortion advocates focused on a different tactic to secure a HLA; calling a constitutional convention.[177] A constitutional convention is a meeting that congress must convene if asked to do so by two-thirds of the states.[178] This tactic would have enabled anti-abortion states to request a convention but bypass the requirement for two-thirds of Congress to support a constitutional amendment proposed via the traditional method.[179]

1977-8 saw several notable incidents of anti-abortion violence at clinics.[180] The data aggregated by economists Mireille Jacobson and Heather Royer includes 1 violent incident in 1976, 4 in 1977, and 7 in 1978.[181] Isolated anti-abortion activists committed many acts of violence during subsequent decades, including arson, bombings, acid attacks, and murder attempts (some of which were successful), although between 1976 and 1983, the average number of violent incidents per year was 3.[182] No major anti-abortion group publicly supported these violent attacks, though some were accused of tacitly accepting violent tactics.[183]

In spring 1979, the American Life League (ALL) was founded after a schism within the NRLC.[184] ALL adopted a more radical stance; in the 1990s, activists from ALL took part in direct action tactics.[185]

In 1979, the organizations Moral Majority (a non-profit), Moral Majority, Inc. (a political lobby) and Moral Majority Political Action Committee were founded by Baptist minister Jerry Falwell, partially on the encouragement of conservative activists such as Paul Weyrich.[186] These groups were part of the developing political mobilization of conservative Christians, which included other groups such as Christian Voice, the Religious Roundtable, and the National Christian Action Coalition. These groups, often referred to collectively as the Christian Right, held anti-abortion beliefs among other socially conservative and pro-religious values.[187] At this time, the audience for religious broadcasts and television shows was growing,[188] and these groups became increasingly politicized.[189] In 1980, the Washington for Jesus rally with many conservative speakers had somewhere between 250,000 and 500,000 attendees.[190] The anti-abortion movement seems to have become more conservative, influenced by the growth of the Christian Right.[191]

By 1980, the NRLC claimed to have an annual budget of $1.6 million.[192]

Momentum seemed to decline for a constitutional amendment to address abortion by the end of the decade; more constitutional amendments related to abortion were proposed between 1975 and 1980 than 1980-2004.[193] From the late 1970s, some members of the anti-abortion movement became more interested in legislation and litigation that incrementally challenged the abortion rights conferred by Roe.[194]

1980-92: Ronald Reagan, the diversification of anti-abortion tactics, and an increasingly anti-abortion Supreme Court

During the 1980 presidential campaign, the Republican platform was strongly anti-abortion, including advocating an amendment to the Constitution to overturn Roe v. Wade. The Democratic platform remained more ambivalent.[195] The Republican position seems to represent a marked institutionalization of an anti-abortion position, compared to the start of the previous decade.[196] Despite competing against two evangelical Protestants, Jimmy Carter and John Anderson (a Republican turned Independent candidate), Ronald Reagan (the Republican candidate) seemed to more fully endorse the political positions of the new Christian Right.

Reagan was elected and became president in January 1981.[197] From January 1981 until January 1987, the Republicans held a majority in the Senate (for the first time since 1954) but the Democrats retained a majority in the House of Representatives.[198] These victories for a Republican party that newly emphasized anti-abortion attitudes presumably made the political prospects of the anti-abortion movement seem more promising. By the mid-1980s, anti-abortion positions seem to have become much more closely correlated with right wing positions on other issues among members of Congress, though this development did not occur suddenly during or following the election.[199]

In 1982, two separate anti-abortion bills were introduced into Congress: the Hatch Amendment and the Helms Bill. Though the amendment was more moderate than the bill, seeking to return abortion decisions to the states rather than to ban abortions outright, neither passed through Congress.[200]

On January 26, 1983, Senator Orrin Hatch proposed another HLA to a congressional committee. By the time it reached a vote in the Senate on July 27, this HLA (the “Hatch-Eagleton Amendment,” following modification by Senator Thomas Eagleton) proposed that the right to an abortion is not secured by the Constitution. In the Senate, the Hatch-Eagleton Amendment received 49 votes for and 50 against, thereby falling 18 votes short of the 67 needed.[201] This was the only HLA to actually be considered by either the House or the Senate.[202]

After this point, proposed legislation on abortion became less radical and the total volume of proposals decreased. By the count of political scientists Scott H. Ainsworth and Thad E. Hall, between 1973 and 1984, 70% of the abortion-related proposals in Congress were nonincremental, meaning that they were efforts to either reverse or codify Roe v. Wade through legislation. The proportion of proposals that were nonincremental fell to 24% between 1985 and 1992, and down further to 13% between 1993 and 2004. The years between 1973 and 1984 saw 445 proposals (i.e. a mean of 37 proposals per year), 1985-92 saw 213 proposals (mean: 27), and 1993-2004 saw 348 (mean: 29). They note that abortion-related constitutional amendments accounted for less than 10% of all abortion-related activity in the House of Representatives in the 1990s, with 12 abortion-related constitutional amendments introduced in the House in that time.[203] Despite this shift towards less radical proposals, legislation continued to fail to pass through Congress with few exceptions.[204]

During the 1980s, there was a growth in the number of crisis pregnancy centers and alternatives to abortion clinics.[205]

In 1982, the first incident occurred with individuals identifying as members of the terrorist anti-abortion group, the Army of God, with the kidnapping of a doctor who provided abortions and his wife.[206]

By the 1984 election, the Republican party platform declared unequivocally that, “The unborn child has a fundamental individual right to life which cannot be infringed.”[207] Reagan was re-elected.[208]

In 1984, the NRLC and Bernard Nathanson, a medical doctor and co-founder of the abortion rights group NARAL who had reversed his views on abortion, co-produced the documentary The Silent Scream. This documentary seemed to prioritize emotional impact over medical accuracy and became widely publicized.[209] In the same year, the NRLC formalized its media department and ran an advertisement in Time magazine. Though this was its first professionally produced advertisement, the NRLC then launched similar adverts in seven “markets” and by 1985, it had sent a five-minute radio broadcast to 300 radio stations.[210] The group was growing at this time.[211]

In 1985, following 2 years of a boycott of the Upjohn Company that NRLC coordinated, the company ceased research into abortifacient drugs, though they continued to sell the abortifacient drugs Prostaglandins.[212]

The years 1984 and 1985 saw the peak of anti-abortion arsons and bombings (30 in 1984, 22 in 1985) and of reported death threats.[213] In 1984, the number of violent incidents jumped up to 29, from 2 in the previous year; the average number of violent incidents per year was 3 in 1976-83, which rose to 20 in 1984-99.[214] From the mid-1980s, direct action tactics were increasingly used. 80% of large nonhospital facilities (providing 400 or more abortions) were picketed in 1985, with 40% reporting an increase from the previous year.[215]

In 1987, the group Operation Rescue conducted “rescue” tactics—direct action to obstruct the operation of abortion clinics—for the first time at a New Jersey clinic.[216]

In 1988, the group led the “Siege of Atlanta” at the Democratic National Convention in Atlanta, getting themselves intentionally arrested and covering up their own identity in order to clog up the courts and jails;[217] 1,300 were arrested.[218]

Although data by individual years is not available for this period, the average number of arrests of anti-abortion activists per year was 1,875 in 1977-89 and 2,266 in 1990-1993. Picketing of clinics was likely rising steeply at this time; the average number of picketing incidents per year was 65 between 1977 and 1989 and 1,379 between 1990 and 1993.[219] Comparing Gallup polls in 1983 and 1985, there appears to have been a small increase in anti-abortion sentiment (from 16% to 21% believing abortion should be illegal in all circumstances), although the increases in violence and direct action were not the only changes in this period and outright opposition to abortion had fallen back to 17% by 1988.[220]

From January 1987 until January 1995, the Democrats held a majority in both the Senate and the House of Representatives.[221] According to one paper, in 1987, the Reagan administration took on a different strategy to deal with abortion issues, focusing on restriction of abortion rather than radical policy change, because views were too polarized on abortion for radical change to be tractable.[222]

In 1988, in Colorado, Michigan, and Arkansas, a majority (60%, 58%, and 52% respectively) of voters endorsed anti-abortion stances in state referendums on related legislation.[223]

In 1988, the NRLC and other anti-abortion organizations notified drug companies that if any company sold an abortifacient drug, they and anti-abortion members of the public would boycott all the products of that company. The threat of a boycott was used to delay the sale of the abortifacient drug RU-486, which was brought to market in France by 1987, but not until 2000 in the US.[224]

The Republican candidate George H. W. Bush won the 1988 election and became president in January 1989.[225] Although Bush had run against Reagan in 1980 for the Republican party nomination while espousing an abortion rights position, he had changed his position in the intervening years and ran on a platform opposing abortion in 1988.[226] In the 1988 election, the Democratic party adopted a clearer stance in favor of abortion rights.[227]

During the 1988 presidential campaign, the former evangelical Protestant minister Pat Robertson ran against George Bush in the Republican primaries but withdrew before the primaries were finished. The following year, the organization Moral Majority was disbanded seemingly due, at least in part, to its failure to build a wide base of support.[228] Combined, these two events represented notable defeats for the political influence of evangelicals. In the 1990s, however, new organizations with a seemingly more moderate character were established.[229]

In 1989, the five-to-four Supreme Court decision in Webster v. Reproductive Health Services returned some power over abortion policy to states, including during the first trimester of pregnancy.[230] In 1990, the case of Ohio v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health (1990) further reinforced the freedom of state restrictions against abortion services.[231] The ruling also saw challenges by some justices to the principles of Roe v. Wade.[232] One paper, using The New York Times mentions of interest group activities in 1985-9, finds evidence of significantly higher-than-usual activity of anti-abortion groups in the quarter year during which the Webster decision was made but not in the quarter year following it.[233] Further analysis suggests that coverage of both the public activities of anti-abortion groups and the activities of the Courts in this period encouraged support for the legal status quo.[234]

By 1989-90, NRLC sent 85% of their campaign donations to Republicans.[235]

One source claims that by 1992, the NRLC still had fewer than 50 employees, though local groups had experienced professionalization, hiring executive directors.[236] Another source claims that by 1980-91, the NRLC “grew from five to fifty employees, and went from $400,000 annual cash flow to $15 million.”[237]

In 1992, the Planned Parenthood v. Casey decision reaffirmed the principles of Roe v. Wade and found unconstitutional a Pennsylvania law that required women intending to have an abortion to inform their husbands.[238] However, the Supreme Court abandoned the trimester framework previously established in Roe v. Wade, instead using a framework of “undue burden.” This allowed more scope for restrictive laws such as parental involvement laws, as long as they were not found by courts to constitute an undue burden.[239]

The Supreme Court decisions of Webster v. Reproductive Health Services, Ohio v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health, and Planned Parenthood v. Casey made state-level anti-abortion legislation more tractable.[240] Alesha Doan notes that “over 400 anti-abortion measures [were] enacted in the states within a ten-year time span.”[241] In the period 1992-2000, the number of states enforcing laws requiring parental involvement in abortion decisions rose from 20 to 32, 12 bans or restrictions on partial-birth abortions were introduced where previously there were none, and the rise in the number of states requiring parental consent rose from “virtually [none]” to 27.[242]

In 1991, a 46 day protest in Wichita, Kansas with 25,000 anti-abortion activists was orchestrated by the group Operation Rescue. This led to the closure of 3 abortion clinics, 3,000 arrests, and a cost of $846,447 to taxpayers.[243] During the April 1992 “Spring of Life” protests at abortion clinics in Buffalo, New York, 615 arrests were made, and the police officials estimated that extra costs came to $500,000. All clinics remained open.[244] Although not giving precise dates, Carol J. C. Maxwell argues, based on the stories told in activist interviews, that during the 1990s, the “middle ground provided by sit-ins (which allowed assertive personal action, tempered by a commitment to nonviolence) diminished, and the opposing extremes persisted… picketing flourished, acts of extreme violence arose, and terrorist tactics increased,” while other activists shifted away from direct action towards legislative and educational actions.[245]

In 1992, the number of newspaper articles discussing abortion reached a peak of over 10,000 articles.[246]

1992-2000: Bill Clinton, declining violence, and declining abortion incidence

The Democratic candidate Bill Clinton won the 1992 election while supporting abortion rights; he became president in January 1993.[247]

Clinton reversed several laws and restrictions on abortion implemented under Reagan and Bush, such as a gag order that had federally-funded family planning agencies from explaining to their clients that abortion was an option. Several of these restrictions have subsequently been reinstated and repealed again as administrations have changed.[248]

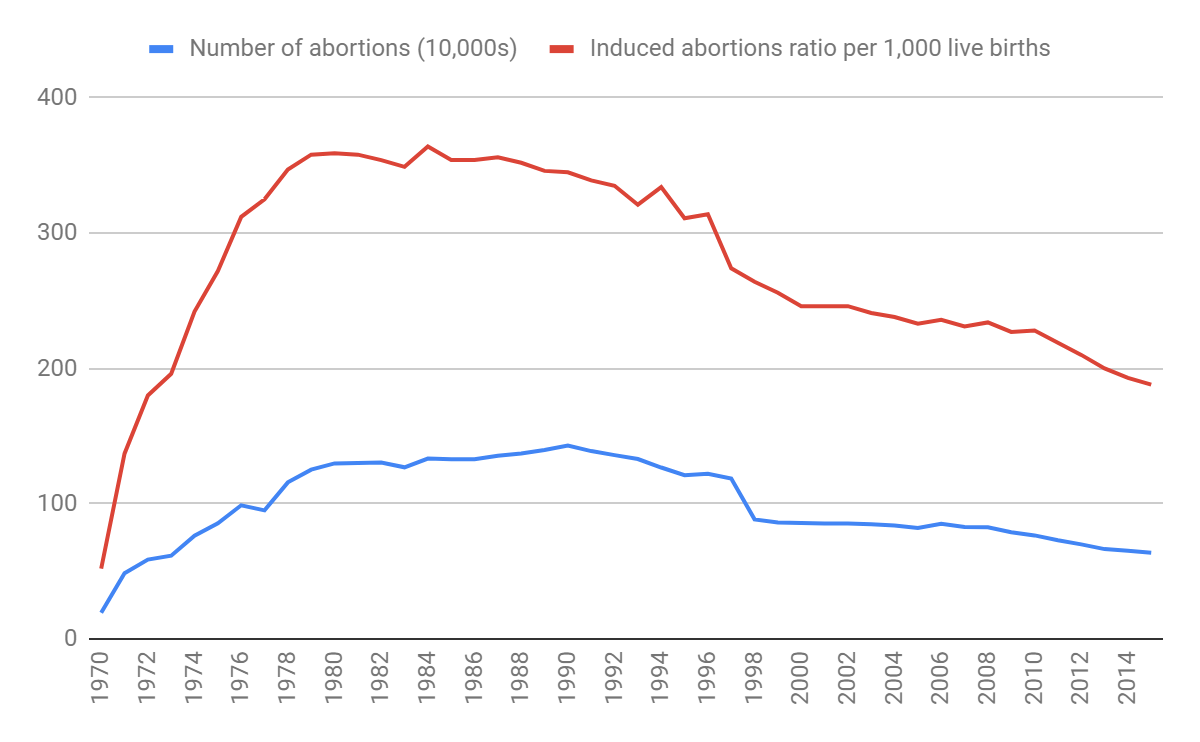

From approximately 1993, a decline in the number of abortions began that has continued until at least 2015.[249] Reported legal abortions dropped 18.4% from 1990 to 1999.[250]

In 1994, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in National Organization for Women v. Scheidler that the existing Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) could be applied to restrict illegal anti-abortion activism.[251] In May 1994, the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act (FACE) was passed, which prohibited the use of force to prevent someone using or providing abortion services, as well as prohibiting the intentional damage of a facility.[252] After 1994, the percentage of clinics reporting to have experienced severe violence and threats of severe violence in surveys (including blockading clinic entrances or facility invasions) dropped steeply.[253] Another Count of violent incidents with a narrower categorization shows that violent behavior peaked in 1992, with 51 incidences of arson, bombings, or acid attacks, though there continued to be more than 10 incidents each year until the year 2000; the average number of violent incidents per year was 20 in 1984-99, which fell to 4 in 2000-4.[254] Data from the National Abortion Federation (based on “monthly reports on the violence and disruption” experienced by NAF members) shows that the number of arrests of anti-abortion activists fell steeply from an average of 2,266 per year in 1990-3 to 217 in 1994 to an average of 8 per year in 1995-2018,[255] presumably because the new legal restrictions made the consequence of risking arrest unacceptably high. Other forms of disruptive activity did not fall at this time, however. In fact, picketing rose from an average of 1,379 incidents per year in 1990-3 to 1,407 incidents in 1994, to an average of 8,071 incidents per year in 1995-2014.[256]

From January 1995 until January 2007, the Republicans held a majority in both the Senate and the House of Representatives (apart from 2001 to 2003, when 50 senators from each party were elected). This was the first time that this had happened since January 1955,[257] well before Roe v. Wade, although Clinton remained president until 2001.[258] Anti-abortion candidates seem to have performed well in the election. One newspaper noted that:

“[N]ot a single pro-life governor or member of Congress of either party was defeated by a pro-choice challenger; pro-life challengers defeated 28 House and 2 Senate incumbents; of the 48 races for open House seats, pro-lifers took 34; of the 11 new senators, all but one are pro-life; and of the 26 percent of the electorate who said, according to a Wirthlin Group post-election survey, that the abortion issue affected the way they voted, two-thirds backed abortion foes while only one third voted for pro-choice candidates.”[259]

In the 1996 election, Republican candidate Bob Dole seemed to de-emphasize abortion issues compared to previous Republican candidates.[260] Clinton was re-elected.[261]

In April 1996 and October 1997, President Bill Clinton vetoed bills banning the procedure of intact dilation and extraction (an abortion procedure in the late stages of pregnancy, widely known as partial-birth abortion) on the basis that they did not include health exceptions.[262]

In 1997, in Schenck v. Pro-Choice Network of Western New York, anti-abortion activist Paul Schenck challenged a US district court injunction which restricted demonstrations from within 15-feet of four abortion clinics in New York state. The case came before the Supreme Court, where Justices ruled 8–1 to uphold the constitutionality of a “fixed buffer zone” (the area around the clinic itself), but not that of a “floating buffer zone” (the area around objects in transit such as cars or people).[263]

The year 1999 saw a high-profile death of a mother during an abortion procedure, which was followed by increased regulations on abortion clinics in “dozens of states;” the AUL claim that “many” used “AUL’s model act as a guide.”[264] Indeed, hundreds of abortion-related bills were proposed in the states each year in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Over 400 anti-abortion measures were enacted within ten years.[265]

In 2000, the US Supreme Court overturned partial-birth abortion bans across 30 states in Stenberg v. Carhart because it made no exception “for the preservation of the... health of the mother” and imposed an “undue burden” on a woman’s ability to choose to have an abortion, both of which violated the principles of the 1992 Planned Parenthood v. Casey ruling.[266]

2000-present: Republican dominance, incremental legislative successes, and renewed anti-abortion sentiment in the Supreme Court

Republican candidate George W. Bush won the 2000 election and became president in January 2001. This was the first time since January 1955 that the president had been a Republican simultaneously with both the Senate and House of Representatives having Republican majorities.[267]

In 2003, in spite of the Stenberg v. Carhart ruling that had overturned state partial-birth abortion bans, Bush signed the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act into law. One paper finds, through content analysis, that although senators mostly voted for or against the bill on the basis of its constitutionality, discussion focused on the morality of the procedure. The author argues that the issue may have been framed in this manner in order to pressure abortion rights politicians and the Supreme Court.[268] In 2007, the Gonzales v. Carhart case upheld the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003 by a vote of 5-4, including by two justices appointed to the Supreme Court by George W. Bush. This modified the earlier findings of Stenberg v. Carhart.[269]

On April 1, 2004, Bush signed the Unborn Victims of Violence Act into law, which meant that those who injured or killed a pregnant mother could be prosecuted with a second offence against the unborn child. This act thereby established the fetus as a separate legal entity.[270] Commentators suggested that this was a strategic decision taken by the anti-abortion movement to establish legal personhood for human fetuses.[271] Legal challenges to similar laws at the state level have been rejected.[272]

From January 2007 until January 2011, the Democrats held a majority in both the Senate and the House of Representatives.[273] Democratic candidate Barack Obama won the 2008 election and became president in January 2009.[274] Despite some legislative and legal victories for the anti-abortion movement, this period of Republican dominance thus came to an end without overturning of Roe v. Wade or implementing any particularly radical reshaping of the abortion policy landscape, which may have been due partially to the Republicans not prioritizing socially conservative goals.[275] From January 2011 until January 2015, the Republicans held a majority in the House of Representatives, but the Democrats retained a majority in the Senate.[276]

By the Guttmacher Institute’s count, 2011 saw a sudden rise in the passage of state laws restricting abortions from between 0 and 30 passed in each year from 1985 to 2010 up to over 90 restrictions passed in 2011 alone.[277] This seems likely to have been encouraged by the new Republican control of the House of Representatives.[278] These laws include TRAP (Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers) laws, as well as restrictions on insurance coverage of abortion procedures, other restrictions on the conditions in which medical abortion can be provided, and bans on abortion after 20 weeks of pregnancy.[279] According to the data from NARAL, however, 2011 seems like less of a sudden rise, with 69 new “statewide anti-choice measures” enacted, while the highest increase in previous years was 58 in 2005. In 2016, the cumulative total enacted since 1995 was 932.[280]

In 2011, the first “heartbeat bills” were proposed.[281] Heartbeat bills are legislation that makes abortion illegal once a heartbeat can be detected. This can be as early as six weeks into the pregnancy, at which point some women may not yet be aware that they are pregnant.[282] These bills therefore seem likely to drastically cut the number of abortions conducted within an individual state where such legislation exists, but fall slightly short of an outright ban on abortion.

From January 2015 until January 2019, the Republicans held a majority in both the Senate and the House of Representatives.[283] Compared to 2014, the years 2015 to 2018 saw very sharp rises in the amount of hate mail and harassment, trespassing, and picketing conducted by anti-abortion activists; each of these activities rose in frequency by over an order of magnitude between 2014 and 2018. For example, the number of picketing incidents rose from 5,402 incidents in 2014 to 99,409 in 2018, with an average of 8,071 per year in 1995-2014 rising to an average of 65,200 per year in 2015-18.[284] These changes do not appear to have had any notable effect on public opinion.[285]

In 2016, the Whole Woman's Health v. Hellerstedt ruling struck down several restrictions on abortion services in Texas via the “undue burden” principle.[286]

Republican candidate Donald Trump won the 2016 election and became president in January 2017. At various points, Trump had announced inconsistent views on abortion.[287] However, during the campaign, he identified as “pro-life” and announced that he intended to appoint anti-abortion Justices to the Supreme Court, which would then “automatically” lead to the reversal of Roe v. Wade.[288] Since then, he has appointed two anti-abortion justices, Neil M. Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh.[289]

In January 2017, Vice President Mike Pence attended the annual March for Life in Washington DC. He was the highest-ranking U.S. official to attend in person, though presidents had previously telephoned in as speakers.[290] In January 2017, the House of Representatives passed legislation that would make the Hyde Amendment’s provisions permanent, preventing the use of certain federal funds for abortions. However, the bill was never brought to a vote in the Senate.[291]

From January 2019 until the time of writing, the Democrats have held a majority in the House of Representatives but the Republicans have retained a majority in the Senate.[292] In February 2019, in the June Medical Services v. Gee ruling, the Supreme Court voted 5-to-4 to prevent a restrictive Louisiana abortion law.[293]

One article by the BBC claims that between January and April 2019, fifteen states “have specifically been working with so-called ‘heartbeat bills,’ that would ban abortion after six weeks of pregnancy,” compared to seven in 2018.[294] In early April, the Guttmacher Institute noted that “Legislation under consideration in 28 states would ban abortion in a variety of ways.”[295] Three heartbeat bills have been passed by state legislatures but struck down by courts or judges, six further bills have been temporarily blocked by federal courts, and one is expected to be effective from November 16, 2019.[296]

Comparing Gallup polls in May 2018 to May 2019, the public seems to have become slightly more hostile to abortion by several percentage points.[297] Abortion issues may also to have become more politically salient in this period; asked to think about “how the abortion issue might affect [their] vote for major offices,” Gallup polls show that 75% of registered voter respondents in 2019 saw abortion as an important issue, compared to 71% in 2016.[298]

Summary of Shifts in Tactics

A broad chronological generalization is that the anti-abortion movement has moved through phases of prioritizing different tactics, shifting each time a tactic failed to achieve success:

- In the 1960s-1973, advocates focused on localized legislation and legal struggles to prevent abortion liberalization.[299]

- In 1973-1983, after Roe v. Wade invalidated localized efforts,[300] advocates focused on major national legislative change such as attempts to introduce a Human Life Amendment and the successful implementation of the Hyde Amendment.[301]

- Once efforts to secure a HLA seemed to have failed despite an anti-abortion Republican president and a Republican majority in the Senate, federal legislative efforts came to focus predominantly on incremental change.[302] Beyond this, various other tactics were used more widely from the mid-1980s, including grassroots direct action to disrupt abortion services and build support for anti-abortion measures,[303] an increase in violent tactics,[304] and a growth in the number of crisis pregnancy centers.[305]

- After restrictions in 1994, grassroots tactics shifted from illegal methods towards legal protest,[306] and the number of violent incidents declined by 2000.[307]

- The 1990s saw a slight increase in the passage of anti-abortion state legislation;[308] this increased again from 2011.[309]

Throughout this period, advocates have also sought to persuade the public that abortion is undesirable and immoral through information campaigns and resources such as John Wilke’s pamphlet Life or Death and Bernard Nathanson’s film, The Silent Scream. The author of this report has not seen evidence to suggest that there were substantial shifts in the extent to which this form of activism was prioritized.

The Extent of the Success of the Anti-Abortion Movement in US

The extent of success is important for the weight that we place on strategic knowledge from this case study. For some concrete outcomes, such as the passage of legislation regulating abortion at the state level, analysis of their causes can provide strategic knowledge.[310] However, where judgements of causation regarding particular movement outcomes are uncertain, a case study can still be informative; if a particular social movement successfully achieves its goals, then this provides weak evidence that its particular characteristics (such as the tactics used and prioritized) led to success. The noting of such correlations between certain characteristics and success or failure will become more useful as we analyze a greater number of historical social movements and note whether any correlations reliably replicate across different movements and across different contexts.[311]

This section seeks to summarize the degree of success or failure of the anti-abortion movement to date, but does not discuss the causes of these outcomes. For discussion of causation, see the section on “Strategic Implications.”

Changes in behavior, legislation, and legal precedent are most directly related to improvements in wellbeing for the intended beneficiaries of a social movement. From a longer-term perspective, reflecting an interest in these changes as constituting one step in a wider process of moral circle expansion or another longer-term social change, it is also important to consider whether the anti-abortion movement has been able to secure less concrete forms of success that might have indirect effects on human fetuses, such as changes to values, culture, and identity.

Given that the anti-abortion movement was partially a reaction to the social and legal changes of the 1960s onwards, the movement may have been successful in terms of preventing change that it disapproved of, rather than in terms of encouraging changes that it desired.

Changes to Behavior

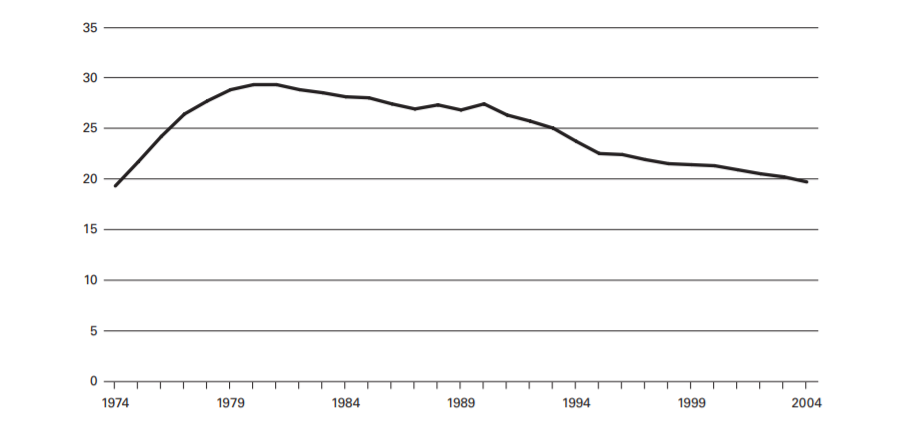

The number of abortions appears to have risen each year between 1972 and 1977, rising from 587,000 in 1972 to 1,270,000 in 1977;[312] this was around the time that the modern US anti-abortion movement began to mobilize seriously, though this process had begun in the 1960s.[313] According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the number of abortions per 1,000 live births rose in the 1970s from little over 200 to around 250 for most of the 1980s. From 1993 this ratio fell and by 2015 was under 200 per 1,000 live births.[314] The extent to which the anti-abortion and abortion rights movements have been responsible for these changes is unclear and so this metric does not show clear success or failure for either movement.[315]

Legislative and Legal Changes

Before Roe v. Wade, there were some political victories for the anti-abortion movement at the state level, which were nevertheless undermined by the legal defeat.[316]

None of the proposals for a Human Life Amendment to overturn Roe v. Wade and/or criminalize abortion have succeeded to date.[317]

Some laws have been passed and Supreme Court rulings have been made that make access to abortion more difficult:

- Although many Supreme Court decisions have mixed implications for accessibility and support for abortion rights, of the 23 Supreme Court decisions relating to abortion between 1973 and 1994, Matthew Wetstein categorized 11 as predominantly supporting or permitting abortion rights and 14 as being anti-abortion.[318]

- The Hyde Amendment and its successful protection in the courts are notable successes of the anti-abortion movement.[319]

- Hundreds of abortion-related bills were proposed in the states each year in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Over 400 anti-abortion measures were enacted within ten years.[320] According to the data from NARAL, in 2016, the cumulative total of “statewide anti-choice measures” enacted since 1995 was 932.[321]

- Three heartbeat bills are expected to be effective by January 1, 2020.[322]

Legal victories may only realize their full potential if further victories are won, by building precedent for further legal decisions.[323]

Acceptance and Inclusion

In various ways, the anti-abortion cause seems to have gained acceptance and normalization within the Republican Party. Four anti-abortion US Presidents—Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, George W. Bush, and Donald Trump—have been elected to date.[324] Vice President Mike Pence attended the annual March for Life in Washington D.C., and presidents have previously telephoned in as speakers.[325] Although not synonymous with the anti-abortion movement, some organizations and individuals associated with the Christian Right have been welcomed by the Republican Party.[326]